After taking a pass on official QE at the Jackson Hole soiree, once again the focus is on the FOMC meeting this week. Will they or won’t they? After last week’s not unexpectedly weak employment number where the BLS birth/death model estimate accounted for 94% of reported headline payroll gains, pundits far and wide raised their percentage bets that QE will indeed be on the Thursday FOMC lunch menu. Personally, I’m convinced weak payroll and capital goods orders as of late are due to business concerns over the as of yet unaddressed fiscal cliff concerns. But the Street remains focused on the apparent self imposed Fed mandate of employment acceleration. The first two mega-QE’s could not light the cyclical employment fire, but hey, maybe the third time is the charm, right? Regardless, we know another Bernanke inspired QE is coming at some point, despite already high food and energy prices, to say nothing of equity prices in a declining earnings growth rate environment.

The point of this discussion is not to debate QE, nor when the next round will be unleashed. I believe that with the upcoming QE, regardless of the mystery date upon which it will arrive, we now need to focus on the banking sector. Why? Because the banks, with emphasis on the very large TBTF banks, are running out of earnings runway fast. Really fast.

Think back to early 2009 as the first QE was being concocted. One of the key rationales for implementation was the thinking that if the Fed could expand its balance sheet and essentially swap fresh cash with banking sector assets, the banks would be free to lend out this new found liquidity. And given the magic of fractional reserve banking, the lending multiplier would respark the core of the modern day global economy – credit acceleration. Without dragging you through an historical retrospective, we all know that despite unprecedented QE1, QE2 and Operation Twist, bank lending in the current cycle has been incredibly subdued. Certainly this is one of the key differentiating factors of the 2009-present cycle. But this becomes very important under QE3. In one sense, based on the character of bank earnings in the current cycle, the moment of truth has arrived. Why? Because the easy earnings gains for the big banks driven by declining loan loss reserves in the current cycle is coming to an end. Couple this with ongoing net interest margin compression (thanks largely to the Fed) and the banks potentially face flat to declining earnings ahead unless lending really starts to accelerate. In fact as you’ll see in the chart below, point to point banking sector earnings have not grown over the last four quarters (FDIC 2Q Bank Report data).

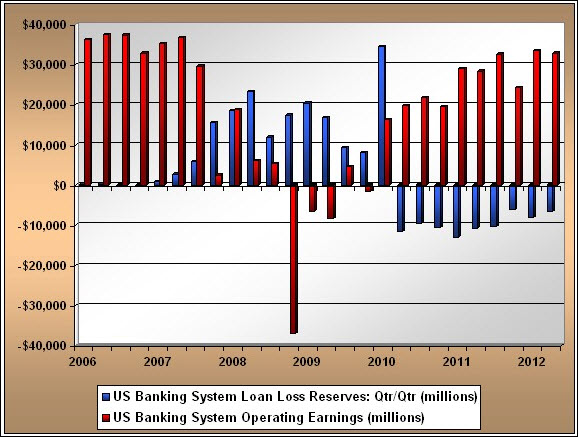

In the chart below, we are looking at quarterly bank operating earnings since 2006. Alongside is the quarter over quarter change in bank loan loss reserves. You can see that in 2006 and early 2007, bank earnings were robust and additions to loan loss reserves small to almost non-existent. Certainly as we moved into 2008 and bank balance sheets became ever impaired, loan loss reserve additions spiked as operating earnings coincidentally collapsed.

But what is absolutely clear is that in the current cycle since late 2009 (the official period of economic recovery), consistent quarterly declines in loan loss reserves have been meaningfully additive to reported earnings. Across the banking system as a whole 35% of reported earnings since 2010 has been a result of loan loss reserve reversions taken into reported earnings.

Although I’ll refrain from dragging you through a good amount of data, loan loss reserve draw downs into earnings have been most meaningful for the TBTF banks. You’ll certainly remember a number of quarters whereby JPM or C “made the numbers” almost exclusively by loss reserve draw downs. The important issue of the moment is that this ability to boost earnings from prior period reserve additions is coming to and end.

Across the banking system loan loss reserves as a percentage of total loans has dropped 125 basis points since mark-to-market accounting was wiped away in early 2009. But if we look at banks based on asset size, it’s the small banks that are still carrying loss reserve ratios quite near their peaks of the last five years, skewing a bit the message of the chart below. For the very small banks, loss reserves as a percentage of total loans have maybe dropped 10 basis points from prior cycle peaks, nowhere near the 125 basis point compression we’ve experienced across the aggregate banking system. It’s the big banks who have been the most aggressive in reducing ongoing quarterly absolute dollar loss reserve provisions and existing loss reserves relative to total loan ratios.

Again, why bring this up now? It just so happens that in 2Q, the US banking system provision for loan losses was close to flat with the prior quarter. Quarterly loan loss provisions have been dropping consistently and meaningfully every single quarter since early 2010 and in 2Q of this year stood 78% below the absolute dollar quarterly provision for loan losses seen at the outset of 2010. Message being with a now flat quarter over quarter loan loss provision? The earnings gains for the banks from reduced loan loss provisions/reserve ratio declines is over. Looking ahead, banking system earnings will now reflect much more core operating fundamentals.

To put a bit of banking sector earnings pressure icing on the proverbial cake, this is occurring alongside a banking sector net interest margin for 2Q 2012 that was as low as anything seen since the third quarter of 2009. We know what the Fed’s grand monetary experiment has done to the money fund complex in the US, or at least what was the money fund complex. Despite their prime directive to protect the banks, certainly the Fed has been the driver of banking system net interest margin compression. Will QE3 only exacerbate the trend?

Thinking about all of this collectively, I believe the key question now becomes, will QE3 finally spark a meaningful acceleration in bank lending? The banks have been able to “hide” behind declining loan loss provisions for close to the last three years, but that will no longer be the case ahead. A steep interest rate curve is not about to magically appear any time soon, again courtesy of the Fed. So the banks are going to face the reality of meaningful reported earnings pressure. Their willingness to lend and their customer’s willingness to borrow will increasingly drive banking sector reported earnings results at the margin in the second half of this year and into 2013. The banks have simply run out of earnings support runway.

So, if QE3 comes to us characterized by Fed balance sheet expansion, will the banks use the newfound liquidity to lend? Or will they simply continue to use it to trade/invest? I suggest that watching bank behavior will be a very important tell regarding the real economic outlook by the banks themselves and very much a statement on their desire to increase balance sheet risk. If QE3 comes and bank lending does not accelerate, then we may see the Fed and Apple in a head to head race to see just which can release version 10 of their latest product first, whether that be a phone or an expanded central bank balance sheet.