“We live in a global economy, so you yourself cannot do something alone. You have to cooperate with your partners.”

– Kim Choong-soo, Governor of the Bank of Korea

“David Lightman: What is the primary goal?

Joshua: To win the game.”

– Dialogue, War Games

“I generally don’t know how far things go, but I can see which way they are going.”

– George Soros

“The fact is, currency wars are fought globally in all major financial centers at once, twenty-four hours per day, by bankers, traders, politicians and automated systems — and the fate of economies and their affected citizens hang in the balance”

– Jim Rickards, Currency Wars

One, two, three, four, I declare a thumb war!”

I was late to the sport of Thumb Wrestling, having spent my childhood playing such games as British Bulldog (sadly, a game deemed too violent for today’s less hardy progeny); but my children, prevented from engaging in any kind of physical contact on the school playground for fear of potentially life-ending knee-scrapes (or, more likely, school-ending legal action) were ardent thumb wrestlers; and I found myself engaged in what to me were rather pointless exercises during which new rules were arbitrarily added to the game, which seemed designed solely to ensure that Dad never won. (I am still not 100% certain what the rules are surrounding the ‘sneak round-the-back-attack’, but that strategy did result in my losing handily to my daughter, Brontë, whenever combat ensued). No matter. Whenever the rhyming gauntlet was thrown down, it was on like Donkey Kong — though the need to explain that particular reference to Brontë meant that I tended to enter the battle feeling rather old and decidedly unfit for combat. My run of defeats was truly epic.

Nobody ever really wins at Thumb Wars, which makes the whole thing rather pointless; and, as it turns out, the same can be said about the subject of today’s discussion — Currency Wars — which seem to be erupting across the globe; and, as they gain in intensity, these monetary conflicts are threatening to throw a major spanner in the works of a world that, until recently, seemed to have been operating under the assumption that it was possible for multiple countries to all devalue their currencies simultaneously in order to inflate their massive debts away.

Poor, misguided fools.

There are many parts of the current financial equation that puzzle me, from investors who are happy to accept guaranteed losses in their government-bond portfolios to governments that genuinely seem to think that increasing their spending by a tiny bit less than they had intended counts as a 'spending cut'; from yield-starved souls who feel that the appropriate return for dipping one’s toe into the junk bond market is sub-6% to business owners who, in a world sloshing in trillions of freshly printed funny money, are forced to pay double-digit interest rates for access to some of the magical bounty.

But beneath it all, at the wellspring of all the disconnects and false price signals that are making investing in today’s supposedly free markets an impossible task, lies the source of my greatest consternation: central banks.

I have one simple question for those august institutions, and it is this:

Do they really think it is possible for them all to devalue their currencies against each other simultaneously and achieve anything but rampant and universal inflation at some future point in time?

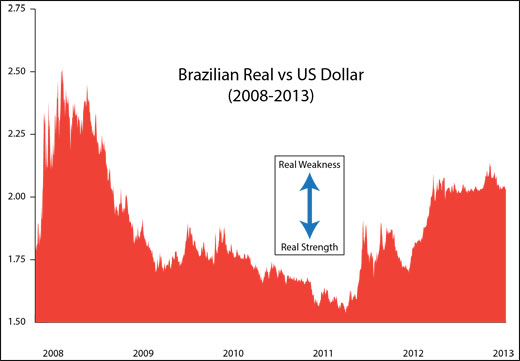

Thus far, the focus on a currency war has been rather diffuse and confined to the fringes of intelligent discussion. The first shot across the bow came way back in 2010 when Guido Mantega, Brazil's finance minister, stepped up to a microphone in São Paulo and broke the central bank omerta:

'We’re in the midst of an international currency war, a general weakening of currency. This threatens us because it takes away our competitiveness,' were Mantega's exact words. Simple. Accurate. Ominous. The FT takes up the story:

(FT): Mr Mantega’s comments in São Paulo on Monday follow a series of recent interventions by central banks, in Japan, South Korea and Taiwan in an effort to make their currencies cheaper. China, an export powerhouse, has continued to suppress the value of the renminbi, in spite of pressure from the US to allow it to rise, while officials from countries ranging from Singapore to Colombia have issued warnings over the strength of their currencies....

By publicly asserting the existence of a “currency war”, Mr Mantega has admitted what many policymakers have been saying in private: a rising number of countries see a weaker exchange rate as a way to lift their economies.

The politics of such an issue were immediately apparent:

The proliferation of countries trying to manage their exchange rates down is also making it difficult to co-ordinate the issue in global economic forums.

South Korea, the host of the upcoming G20 meeting in November, is reluctant to highlight the issue on the gathering’s agenda, also partly out of fear of offending China, its neighbour and main trading partner.

That was then, and at the time most 'policymakers' (unsurprisingly) as well as most journalists, or 'commentators' (as they are often called in such matters), opined that the term currency war overstated the extent of the hostilities. Any chance of such a conflict was ... 'contained'. You know, like that 'little subprime problem'.

The tools available for competitive devaluation begin with good old-fashioned jawboning. After all, why waste valuable reserves when markets can be scared or cajoled into a suitable reaction by a few choice words from a central banker armed with the necessary gravitas. Ain't that right, Mario?

Next up is the euphemistic process of 'intervention' in currency markets. This is, of course, aimed purely at manipulation 'stabilization'. From there, we move on to a mish-mash of interest-rate policies, capital controls, and something quite innocuously called 'quantitative easing', aka 'money printing', about which we have all heard quite a lot in recent times.

(Rant on: Incidentally, I have had enough of the whole business of trying to continually soften or find new and less-offensive phrases for just about everything that has invaded every corner of modern life. The final straw came this week when I discovered that the humble tracksuit worn by soccer players when warming up before a match is now called an 'anthem jacket'. Why? Because they happen to be wearing it as the national anthem is played. IT'S A TRACKSUIT. Please. Somebody. Make it stop. Rant off.)

Anyway, back to Currency Wars.

The 16-year period between 1995 and 2010 saw a huge shift in the world's currency reserves from West to East (a theme we will certainly return to this year), as can be seen from the chart below. During that period, emerging economies took advantage of shifting trade patterns to accumulate enormous foreign reserves, largely at the expense of their Western customers; but this explosion in their holdings can be traced back to the Fed's ridiculous 'lower for longer' approach to interest-rate policy, which persisted from the mid-1990s to ... well, I'll get back to you when I can fill in the back-end number, but suffice to say, it won't be any time soon.

Where did that explosion in reserves come from? Well, some of it came from good old-fashioned growth (remember that?). The vast majority rest? Well, that would be debt — you know, 'debt', the remedy currently being prescribed to fix the problem of too much debt? Yeah, that.

By the time July of 2011 rolled round, despite a period of relative calm, Mantega was still banging the currency war drum as he watched the Brazilian real continue to strengthen against Bernanke and Geithner's much-desired 'strong' dollar:

(FT): Brazil is preparing a range of additional measures to stem the damaging rise of the real as the global currency war shows no signs of ending, according to Guido Mantega, the country’s finance minister...

Mr Mantega said the Group of 20 leading economies was still a long way from achieving its goal of agreeing new guidelines for managing currencies, there were 'struggles between countries' such as the US and China, and the global currency war was 'absolutely not over'.

'Absolutely not over'. No, it wasn't. In fact, it was just getting started.

The problems for emerging markets facing concerted efforts by slowing, debt-laden economies to weaken their currencies are well-known.

Slow growth and low interest rates in advanced economies continued to put upward pressure on Brazil’s currency, Mr Mantega said, forcing the authorities to consider further intervention in currency and derivatives markets to limit overshooting.

'We always have new measures to take,' he told the FT, indicating on the sidelines of an investor conference that these would not be pre-announced, but would include market intervention.

The relative strength of their currencies is a big issue for fast-growing economies. Too strong and, though the domestic market will struggle to overheat, competitiveness is impaired. Too weak and the reverse is true, but inflation becomes a serious issue. The answer, of course, is what used to be referred to as the 'Goldilocks' outcome. This term was quite popular until the subprime crisis made fools of everyone who predicted it as the likely endgame to the clear and present dangers facing the US economy. I would, in fact, venture to suggest that the disappearance of that particular term from the punditocracy's lexicon is perhaps the one good thing to have come out of the events of 2007-8.

But, as always, I digress.

It used to be that a government would decrease the value of its currency by literally devaluing it — reducing its intrinsic value by lowering the amount of gold (or silver) from which coins were minted; but that was in a time devoid of fiat currencies and when there was extremely limited international trade, so exchange rates were of little or no importance. It was a time of hard money and gold standards.

The first great currency war occurred, coincidentally of course, during the Great Depression, when most countries abandoned the gold standard; and Britain, France, and the USA set off on a competitive devaluation process driven by sky-high unemployment (you'll stop me if any of this stuff sounds familiar, right?). As countries devalued against each other in the attempt to reinvigorate their export economies at the expense of their trading partners, nothing was really achieved (except that countless trading companies were bankrupted by wildly gyrating short-term exchange rates). This period in history is beautifully chronicled in Liaquat Ahamed's Lords of Finance (see left), a staggeringly good book from which I have often quoted in these pages. If you haven't read it, read it!

The Bretton Woods era, which ran from the end of WWII until August 15, 1971 (roughly) meant that, with gold anchoring a group of semi-fixed exchange rates, competitive devaluation was more or less negated; and, though the Plaza Accord, signed in 1985, brought about a major devaluation of the US dollar against the yen and Deutsche Mark, it necessitated the Louvre Accord two years later to halt the dollar's slide (you just gotta LOVE these bankers).

The Asian currency crisis of 1997 contained the seeds of an East vs. West currency conflict, but catastrophe was averted, despite the damage that was done to the US deficit and the seeds that were sown for a decade-long war of words between the US and China — all of which brings us right back to today and the currency war that is just getting going.

Whenever such things are talked about, it is invariably in the context of the US dollar; but the trade war I want to take a look at specifically is the one brewing in my part of the world, between two powerhouses who bear considerable enmity towards one another. No, not China and Japan (that has the makings of a war of an altogether different kind), but Korea and Japan.

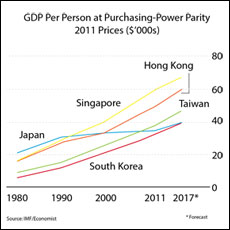

The rather unfortunate-looking vehicle (left) is the Sibal — the first car ever produced in South Korea. It was developed by the Choi brothers in 1955 and was based (as you can clearly see) on the chassis of the Willy's Jeeps left behind by departing US troops — only about 50% of its parts were locally produced.

This put the Korean automobile industry about 40 years behind that of Japan, whose storied zaibatsu (conglomerates) began building in the 1910s the cars that would eventually come to dominate the world.

The other area where Japan had it over Korea was consumer electronics.

Back in the 1980s and into the 1990s, companies such as Sony, Pioneer, Hitachi, and Sharp were producing consumer electronics widely recognized as the best in the world; and alongside the likes of Toyota, Nissan, and Honda they helped Japan Inc. stand astride the world.

Back then, Korean cars and consumer electronics were, frankly, a bit of a joke.

Nobody who could afford not to would buy a Daewoo or a Hyundai car. Nobody wanted an LG television. In fact, in 1981 Samsung Electric (the forerunner to Samsung Electronics) proudly boasted that it had manufactured its 10 millionth black & white TV.

Fast forward to 2012, and the change in the landscape has been nothing short of seismic.

Sharp sits on the verge of bankruptcy, once-mighty Sony has seen its share price plummet and is now the subject of speculation as to who may buy it and Hitachi is known more for computer disk drives than consumer electronics. Meanwhile, Samsung Electronics is the only company in the world giving Apple a run for its money.

Samsung surpassed Sony in 2005 to become the world's 20th-largest brand, and by 2012 it had not only become the world's largest-selling mobile phone company (some feat in today's Apple-dominated world) but had spent a brief period in 2007 as the world's largest technology company, when it leapfrogged the then-incumbent, Hewlett-Packard.

How did all this come about? Simple:

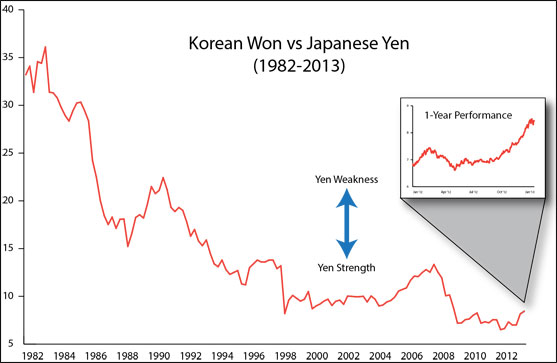

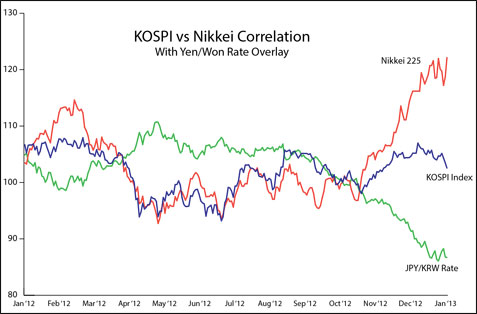

As the yen strengthened due to its anchor role in the carry trade, the won weakened substantially, making Korean products far cheaper than those of their Japanese counterparts. Simultaneously, the quality of Korean cars and consumer electronics was improving dramatically, enabling Korean consumer electronics to sweep past those of Japan and their car industry to reach heights never dreamed of when the Choi brothers cobbled together the Sibal, as a look at the best-selling cars of 2012 demonstrates:

✔1. Toyota Corolla (Japan)

✔2. Hyundai Elantra (Korea)

✔5. Kia Rio (Korea)

✔8. Toyota Camry (Japan)

Having been gifted a huge headstart by Japan, South Korea is not about to allow the Japanese to claw that advantage back by standing still and letting them weaken the yen, as was made apparent by comments from South Korea's finance minister, Kim Choong-soo, in Davos this past week:

(CNBC): Basically, the level of foreign exchange has to be determined by market fundamentals in the medium to long-run. But in the short run, we all know that there are times where noises can matter, disturbances can take effect. But that's only for the short-term period," Kim told CNBC on the sidelines of the WEF in Davos.

"We all know the grave consequences of competitive devaluation efforts, which we experienced some decades ago. So I think it's time to sit together to talk about that. We live in a global economy, so you yourself cannot do something alone," Kim said. "You have to cooperate with your partners."...

Asked whether South Korea would be forced to respond to the Bank of Japan by managing the won in a more meaningful way for the country's manufacturers, Kim said: "It all depends upon how markets respond to such moves, and the markets have changed over time… our central bank will do whatever it's supposed to do to protect the high volatilities in the financial sector."

"And I'm particularly concerned about the volatilities. If changes are made too rapidly, we all know that will create uncertainties, and we have to do something to prevent that from happening," Kim added.

Japan's currency has been strengthening for two decades, while its competitors have been happy to sit back and let the weakening effects of that move on their own currencies continue. Now Japan has decided it needs a weaker yen, and though the move has thus far been fairly powerful, we have reached the point where the likes of Korea will step in and defend the advantage they have gained over the last twenty years. As can clearly be seen from the graph (previous page), Korea's KOSPI Index has decoupled from the Nikkei as the yen slide has picked up speed, and that is a phenomenon South Korea simply cannot allow to continue.

This is how it starts with Currency Wars.

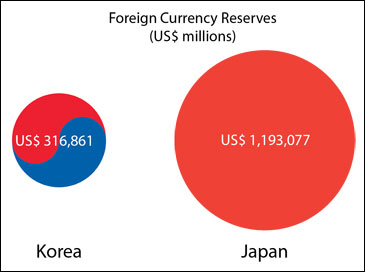

When it comes to ammunition reserves, Japan's balance sheet dwarfs that of Korea, with almost four times the amount of foreign currency at their disposal; but they will be fighting this currency war on multiple fronts, and those reserves can quickly become exhausted.

Printing money or devaluing your currency in a vacuum is one thing. Generally, you can make a difference up to the point where those against whom you are attempting to weaken push back (ask the Swiss National Bank); but once it becomes a competitive sport, all bets are off.

This past week, Japan announced that, as of January 2014, it will begin an open-ended, unlimited QE program to monetize Japanese debt (they are currently buying 36 trillion yen a month, or about 0 billion) and attempt to generate the magical 2% inflation that will decimate its bond market solve all its problems. Sadly, this does no more than allow Japan to catch up with other central bankers around the world who are already monetizing like crazy; but, purely on the basis that something is better than nothing, this change in policy has been cheered to the echo.

As we head into 2013, we find ourselves in a situation unlike any that has ever occurred in the history of global finance. The ability to simplify the complexity of that situation is something only the very brightest amongst us are able to do, and one such man is Raoul Pal of the Global Macro Investor (with whom I have recently been fortunate enough to have a fascinating dialogue). Raoul put together a very simple list which, at the time he compiled it in late December, beautifully highlighted the utter absurdity of today's central banking folly.

The list was split into sections that grouped the 38 countries that had negative or zero real rates (yes: THIRTY. EIGHT.), as well as the countries that either had explicit QE programs in place or were actively intervening in or verbally manipulating their currencies:

Source: Raoul Pal, Global Macro Investor

Now, does it seem remotely possible that all these countries can have weak currencies at the same time? Of course it isn't possible. Not without rampant inflation, it isn't. But that doesn't appear to be a problem for the central bankers of the modern world, who are confident that inflation is 'contained'. Yes, 'contained'. Is anyone paying attention, I wonder?

The competitive devaluation merry-go-round will continue, because these buffoons have left themselves no other options. A currency war will break out in earnest; because none of them will be able to generate the weaker currency they need, and that will in turn lead to several exits from the EU, because the weaker economies will need to regain control of their own currencies and not be beholden to Brussels. This is the way things go, I am afraid.

"One, two, three, four, I declare a currency war!"

There is one other important piece of Currency Wars that I want to take a look at before we wrap things up for the day, and it stems from a rather interesting recent announcement from the Bundesbank.

Last October, the Bundesbank was challenged by auditors to explain why they kept the majority of their gold overseas. They explained it rather neatly:

(ZeroHedge): The reasons for storing gold reserves with foreign partner central banks are historical... To be more specific: in October 1951 the Bank deutscher Länder, the Bundesbank’s predecessor, purchased its first gold for DM 2.5 million; that was 529 kilograms at the time. By 1956, the gold reserves had risen to DM 6.2 billion, or 1,328 tonnes; upon its foundation in 1957, the Bundesbank took over these reserves. No further gold was added until the 1970s. During that entire period, we had nothing but the best of experiences with our partners in New York, London and Paris. There was never any doubt about the security of Germany’s gold. In future, we wish to continue to keep gold at international gold trading centres so that, when push comes to shove, we can have it available as a reserve asset as soon as possible. Gold stored in your home safe is not immediately available as collateral in case you need foreign currency. Take, for instance, the key role that the US dollar plays as a reserve currency in the global financial system. The gold held with the New York Fed can, in a crisis, be pledged with the Federal Reserve Bank as collateral against US dollar-denominated liquidity. Similar pound sterling liquidity could be obtained by pledging the gold that is held with the Bank of England.

So there you have it. The Bundesbank was extremely happy with holding its gold in New York (amongst other places) and saw no need to move it.

A couple of weeks later, the story surfaced again when Andreas Dobret of the Bundesbank gave a speech in front of the NY Fed's Bill Dudley:

(Zerohedge): Please let me also comment on the bizarre public discussion we are currently facing in Germany on the safety of our gold deposits outside Germany — a discussion which is driven by irrational fears.

In this context, I wish to warn against voluntarily adding fuel to the general sense of uncertainty among the German public in times like these by conducting a “phantom debate” on the safety of our gold reserves.

The arguments raised are not really convincing. And I am glad that this is common sense for most Germans. Following the statement by the President of the Federal Court of Auditors in Germany, the discussion is now likely to come to an end — and it should do so before it causes harm to the excellent relationship between the Bundesbank and the US Fed.

Throughout these sixty years, we have never encountered the slightest problem, let alone had any doubts concerning the credibility of the Fed [ZH may, and likely will, soon provide a few historical facts which will cast some serious doubts on this claim. Very serious doubts]. And for this, Bill, I would like to thank you personally. I am also grateful for your uncomplicated cooperation in so many matters. The Bundesbank will remain the Fed’s trusted partner in future, and we will continue to take advantage of the Fed’s services by storing some of our currency reserves as gold in New York.

Pretty clear, it has to be said. No chance the Bundesbank would be repatriating their gold any time soon. Except...

On January 16, 2013, just a matter of weeks after their earlier assertions, the Bundesbank released the following statement:

By 2020, the Bundesbank intends to store half of Germany’s gold reserves in its own vaults in Germany. The other half will remain in storage at its partner central banks in New York and London. With this new storage plan, the Bundesbank is focusing on the two primary functions of the gold reserves: to build trust and confidence domestically, and the ability to exchange gold for foreign currencies at gold trading centres abroad within a short space of time.

The following table shows the current and the envisaged future allocation of Germany’s gold reserves across the various storage locations:

To this end, the Bundesbank is planning a phased relocation of 300 tonnes of gold from New York to Frankfurt as well as an additional 374 tonnes from Paris to Frankfurt by 2020.

The withdrawal of the reserves from the storage location in Paris reflects the change in the framework conditions since the introduction of the euro.

Given that France, like Germany, also has the euro as its national currency, the Bundesbank is no longer dependent on Paris as a financial centre in which to exchange gold for an international reserve currency should the need arise. As capacity has now become available in the Bundesbank’s own vaults in Germany, the gold stocks can now be relocated from Paris to Frankfurt.

Of course, no sooner had this story hit the wires than all hell let loose as the conspiracy theorists went on the rampage. Rumours swirled around of missing gold, rehypothecation, and massive price spikes as the Fed scrambled to get delivery of Bundesbank gold long ago leased into the market; but finding out the truth about the situation will likely take considerable time.

The important point about the Bundesbank move is that it heightens another form of currency war — one that involves the only REAL currency, gold — that began in August of 2011.

As I wrote back then, when Hugo Chavez demanded his 99 tons of gold from the Bank of England:

(TTMYGH August 26, 2011): Chavez’s move this week could set in motion a chain of events whereby Central banks who store the bulk of their gold overseas in ‘safe’ locations scramble to repossess their country’s true ‘wealth’. If that happens, the most high-stakes game of musical chairs the world has ever seen will have begun.

One would imagine that a country’s gold would be stored onshore in their own vaults rather than be entrusted to a foreign power — after all, if tensions WERE to rise between the two sovereigns, amongst the first casualties would be said gold.

Based on the paper prepared for the Venezuelan Finance Ministry and Central Bank (table, page 3), Chavez is about to ask a group of Western banks to hand over some .1 billion in gold bullion and, despite the obvious logistical nightmare that the transportation of this bullion presents, he will be expecting it to be delivered either to the Venezuelan Central Bank vault, or that of a ‘friendly’ nation such as China or Russia. Soon.

For the longest time, conspiracy theories about the amount of gold actually held in the various depositories have abounded — in fact, we have discussed many of them in these pages over the past couple of years — but now we may finally find out just what does lie beneath, as Venezuela’s grab for their gold could potentially start a landslide of demands for delivery that could unravel a web of deceit years in the making.

Or it may not. Either way, we MIGHT just find out who was right and who was wrong and be able to put the matter to rest once and for all. To quote Vizzini, it would be ‘inconceivable’ to think for a second that central bank governors the world over are blissfully unaware of the rumours about empty vaults, massive leasing programs, and fictitious allocations held on their behalf at places like Fort Knox, the Federal Reserve, and the Bank of England; so one can reasonably imagine that quite a few of them are sitting uneasily in their chairs waiting to see what the response is to the Venezuelan demands.

Personally, if I were a central bank governor, I know I would want to be absolutely certain that my gold was (a) exactly where it was supposed to be, (b) held in the amount advertised and (c) ... well ... made of gold, ideally — as opposed to tungsten.

If there is ANY delay in repatriating Venezuela’s gold, it could potentially start a frantic scramble by central banks to claim their physical gold; and if that happens you can be assured that a fire will be lit under the gold price, the likes of which we haven’t yet seen — even as gold has appreciated from 0 to 50 over the past 11 years.

As it turned out, of course, there was no delay in repatriating Chavez's gold (which is good), but for Germany to pull the same move takes the game to a whole new level, based on the size of their holdings. They estimate that (for unexplained reasons) it will take them 7 years to repatriate the 8% of their gold that they intend moving from the Fed, so answers on that matter will be a long time in coming — unless of course, other central banks decide that Currency Wars is a game they need to get good at.

Earlier in this piece, the chart of currency reserves demonstrated just how swiftly developing markets have been accumulating fiat currency in the last 15 years. A look at what those same central banks have been doing with their gold is highly instructive (not to mention very familiar).

Yes, emerging-country central banks are accumulating gold just as fast as they possibly can, as insurance against problems in the world of fiat currency; and those problems are liable to get bigger with each crank of the printing press.

It was Chavez's announcement that sent gold spiking to ,900 back in September of 2011. Further announcements of similar actions in the wake of Germany's momentous decision may well have a similar effect.

But as I close this week I will leave the final word, appropriately enough, to the man whose book Currency Wars: The Makings of the Next Global Crisis is an absolute must-read on the subject — Jim Rickards:

(Yahoo): Germany made even bigger splash than Japan in the gold market recently with its surprise announcement last week that the Bundesbank would begin repatriating gold reserves held overseas. The central bank said it wanted to keep more than 50% of its gold reserves at home, up from slightly less than one-third currently. With that in mind, the Bundesbank will move all its gold reserves now held in Paris back to Germany, and reduce its reserves held in New York City.

“Germany is saying that gold is money,” says Jim Rickards... Otherwise... they would just leave the gold where it currently is stored.

And Germany isn’t alone. There’s talk that the Netherlands and Azerbaijan will also repatriate gold reserves.

China, the second largest global economy but the sixth largest holder of gold, according to the World Gold Council, is increasing its gold reserves, Rickards tells The Daily Ticker.

“If the Chinese repeat their pattern, I expect late this year or early 2014 the Chinese will announce, ‘We’ve got 3,000 tons or maybe 4,000 tons.’ That will be a shock because suddenly the world will wake up and say why is China buying all this gold?" says Rickards.

He says the reason is obvious: “Gold is the real base money.”

“In dollar terms gold hasn’t gone up that much lately, but in yen terms — with the devaluation of the yen, gold is partly a function of the currency wars,” he says.

Yes Jim, gold is very much a part of Currency Wars, and the competition is just getting started.

*******

Before I run you through what you will find in this week's Things That Make You Go Hmmm..., a quick piece of housekeeping:

I will once again be speaking at the Cambridge House California Resource Investment Conference in Indian Wells, CA, on February 23/24th; and the line-up this year is fantastic.

Rick Rule, Greg Weldon, Frank Holmes, and Peter Schiff will all be in attendance, along with my great friends Al Korelin and John Mauldin; so if you are in the vicinity and would like to drop by and hear from any of these fine speakers, you can find all the details at the conference's website HERE

I hope to see some of you there.