FINANCIAL CRISES AND NEWTON’S THIRD LAW

Sir Isaac Newton knew a thing or two about physics. In one example of his genius, he demonstrated that the same force that causes things to fall to earth, gravity, also keeps the planets in motion around the sun. How did he manage that? Well, like all great scientists, he excelled at the scientific method. For those not familiar, the fundamental precepts of the scientific method are the following:

- Begin with an observation or experience

- Form a conjecture (or hypothesis)

- Make a specific prediction based on the conjecture

- Design an experiment to test the conjecture

If all goes according to plan and the experiment confirms the prediction based on the conjecture, then you have a theory. The scientific method, properly followed, must also allow for others to reproduce the experiment and obtain similar results. However attractive a theory may be at first glance, if it cannot be independently and repeatedly verified in a controlled manner, it cannot properly be called a scientific theory; it remains a conjecture only. In the event that the experiment produces inconsistent results over time, then either the theory needs to be modified or a new conjecture conceived. It is important to remember that science does not purport to "prove" things in an absolute sense, even though well-established theories are referred to as "laws". Theories—even those achieving "law" status, must be "falsifiable" through experimentation. From time to time, they are.

Many are familiar with the apocryphal story of how Newton came to arrive at his conjecture of a force of universal gravitation operating both on earth and in the heavens: Whilst daydreaming beneath an apple tree, staring up at the sky, an apple fell down on to his head. Thus startled, it seemed in that moment as if the apple had fallen right out of the heavens... Regardless of whether this pretty fable is correct, once Newton had made his conjecture he needed to design an experiment to test his predictions. Fortunately it was already widely known at what rate of acceleration objects fall to earth; and the work of Johannes Kepler some years before had demonstrated the relationships between the distance of planets to the sun and the speed and size of their orbits. The experiment, as it were, had already been performed, only in separate pieces that no one had thought to combine. All Newton had to do was to put pen to paper and show that the same equation predicted both the rate at which objects fall to earth and Kepler’s laws of planetary motion. He was referring to Kepler, among others, when he made his famous, humble claim that his achievement was nothing more than "standing on the shoulders of giants." Indeed. Yet he too was a giant.

It would be over two centuries before Newton’s "law" of universal gravitation would be disproved via the scientific method. Albert Einstein did so with his theories of relativity. Fast forward to today: Apparent discrepancies between the predictions of relativity and the observations taking place in particle accelerators are significant enough that many scientists believe that even the theory of relatively will be shown, in due course, to be inaccurate. The search for truth, at least via the scientific method, is still very much on.

Newton was known for much more, of course. His third law of universal motion was that for each and every action there is an equal and opposite reaction. While applicable to the natural world, it does not hold with respect to the actions of financial markets and the subsequent reactions of central banks and other regulators. Indeed, the reactions of regulators are consistently disproportionate to the actions of financial markets. In sinister dialectical fashion, the powers assumed and mistakes made by policymakers tend to grow with each crisis, thereby ensuring that future crises become progressively more severe.

***

Things were looking rather grim for the US economy in mid-1987, soon after Paul Volcker left his job at the helm of the Federal Reserve. The dollar was falling, fast. Inflation and inflation expectations were rising. It was clear that the Fed was going to need to start raising interest rates soon, perhaps sharply. Having successfully broken the back of inflation and supported the dollar in the early 1980s with monetary targeting, double-digit interest rates and the most severe post-WWII recession to date, financial markets were naturally increasingly fearful that the Fed might follow a similar if less severe script again. While the exact trigger will perhaps never be known, this was the fundamental background that led to the great stock market crash of 19 October 1987, on which day the Dow Jones Industrial Average declined by 23%.1

A falling dollar was part of the fundamental background of the 1987 crash

Source: Federal Reserve

Alan Greenspan, a veteran of US economic policy-making circles but a neophyte at the Fed, sensed correctly that an emergency easing of interest rates and other liquidity-enhancing measures would help to restore confidence in the equity market and prevent a possible recession. Sure enough, equity markets bounced sharply in the following days and continued to climb steadily in the following months. It was most certainly a baptism by fire for Greenspan and one which, no doubt, taught him at least one important lesson: If done quickly and communicated properly to the financial markets, emergency Fed policy actions can provide swift and dramatic support for asset prices. But what of the consequences?

While Greenspan might consider this his first, great success, was the Fed’s policy reaction to the 1987 crash proportionate or even appropriate? Was it “an equal but opposite reaction” which merely temporarily stabilised financial markets or did it, in fact, implicitly expand the Fed’s regulatory role to managing equity prices? Indeed, one could argue that this was merely the first of a series of progressively larger “Greenspan Puts” which the Fed would provide to the financial markets during the 18 years that the so-called “Maestro” was in charge of monetary policy and, let’s not forget, bank regulation.

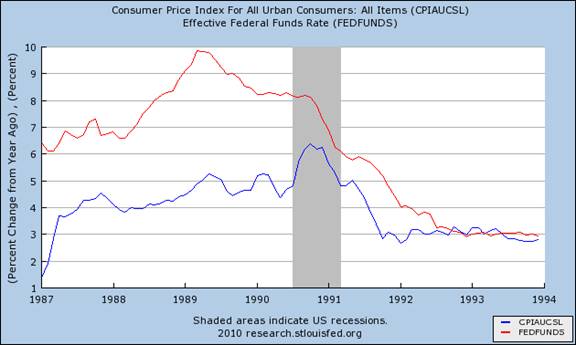

Having received a shot in the arm from the abrupt easing of monetary conditions in late 1987 and combined with the lagged effects of a much weaker dollar, US CPI rose to over 5% y/y in early 1989 and the Fed raised rates in response, eventually tipping the economy into a recession. One aspect of the 1990-92 recession that received much comment and analysis was the “double-dip”. Whereas the initial phase of the recession looked like a fairly typical business investment and inventory cycle, the second phase was characterised by a general “credit-crunch” that constrained growth in most areas of the economy. What was the cause of this credit-crunch? Why, the long-forgotten Savings and Loan crisis of course.

The American dream of homeownership, although associated with the US economy’s capitalist tradition, is apparently something that cannot be achieved without ever-growing government regulation and subsidies. Politicians just love finding ways to assist their constituents with home purchases. In some cases, there is so much government “help” available that homeowners end up owning homes they can’t afford. In the 1980s, Congress decided that, in order to help make housing more affordable, it would ease certain regulations previously restricting the lending activities of Savings and Loans. Credit would thereby become more widely available to a range of borrowers who previously might not have qualified. Importantly, this included risky commercial lending.2

Seeking higher returns, some S&Ls broadened their lending activities, expanding their balance sheets and focusing more and more on the riskiest, most lucrative opportunities. As S&Ls were financed primarily by deposits, they needed to offer more attractive deposit rates to expand. But because all deposits were insured in equal measure by the FSLIC (the Savings and Loan equivalent of the FDIC), depositors would shop around, seeking out the best rates. Deposits therefore flowed from the more conservative to the riskiest institutions offering the highest rates on deposits—fully insured, of course. Some of the most aggressive S&Ls went on a shopping spree, snapping up their more conservative counterparts and deploying their newly-acquired deposits into the latest, greatest, high-risk, high-return ventures.

The results were predictable. By the late 1980s, a huge portion of the S&L industry was insolvent. The recession of 1990-91, made a bad situation worse. FSLIC funds were rapidly depleted. But a federal guarantee is supposed to be just that, a guarantee, so Congress put together a bailout package for the industry. A new federal agency, the Resolution Trust Corporation (RTC), issued bonds fully backed by the US Treasury and used the proceeds to make insolvent S&L depositors whole.

All of this took awhile, however, and as the bad assets of the S&Ls were being worked off, the economy entered part II of the “double dip” and the credit-crunch intensified. The Fed, however, knew what to do. By taking the Fed funds rate all the way down to 3%, real interest rates were effectively zero for the first time since the 1970s. The Fed then held them there for nearly two years, finally raising them when it was absolutely clear that the economy was recovering strongly and the credit-crunch was over in early 1994.

US real interest rates were effectively zero in 1992-93

Source: Federal Reserve

Fast-forward a decade. We all know that the origins of the most recent boom/bust in housing and credit generally can be traced back to the highly accommodative Fed policy implemented in the wake of the dotcom bust in 2001-2003. By late 2003 there was clear evidence that the US housing market was surging and, alongside, homeowners were extracting record amounts of equity from their homes, thereby stimulating the broader economy. However, amidst relatively low consumer price inflation, the Fed determined—incorrectly we now know—that interest rates should rise only slowly notwithstanding the surge in asset prices. With the Fed moving slowly and predictably, risk premia for essentially all assets plummeted. Greenspan referred to the “conundrum” of low term premia for bonds. But low credit spreads and low implied volatilities for nearly all assets were clear evidence of inappropriately loose Fed policy all the way into 2007. By the time the subprime crisis hit in mid-2007, the economic damage had been done. There had been vast overconsumption at home and overinvestment abroad resulting collectively in perhaps the most monumental global misallocation of resources in history. There was no avoiding the crash; the new challenge quickly became how to prevent a complete collapse of the financial system. At this point, the crisis acquired an overt political dimension as taxpayers were asked, in various direct and indirect ways, to bail out those institutions at risk of insolvency and default.

In retrospect, the entire S&L debacle, from its origins in regulatory changes and government guarantees, through the risky lending boom, bust, credit crunch and fiscal and monetary bailout can be seen as a precursor to the far larger global credit bubble and bust of 2003-present: Just replace the S&Ls with Fannie/Freddie and the international shadow banking system. But there is no need to change the massive moral hazard perpetrated by incompetent government regulators, including of course the Fed, and the reckless financial firms who played essentially the same role in both episodes.

See the pattern? For every crisis there is a bailout: S&P index 1987-present

Source: Standard and Poors; Amphora Capital LLP

Those at all surprised by current efforts by the Fed and other regulatory bodies to expand their power over the financial system and the economy in general have not been paying attention to history: For every market action there is a disproportionate regulatory and monetary policy reaction which increases the moral hazard of the system. History may not repeat but it certainly rhymes.

WHY FINANCIAL GENIUS FAILS

The dustbin of financial history is littered with examples of failed genius. LTCM (1998) is a high-profile example, but there are many more. No doubt there were also clever folks involved in running the Knickerbocker Trust (failed 1907), Austrian Kreditanstalt (1931), Continental Illinois National Bank (1984), over 1,000 US S&Ls (1986-91), Barings (1995), and of course Bear Stearns, Lehman Brothers and Merrill Lynch (2008). Perhaps even cleverer people were running the various hedge funds and funds-of-funds which were forced for one reason or another to close their doors in the latest crisis. As we know, in recent years, huge numbers of maths, science and engineering PhDs entered into the financial industry and went to work building subprime CDOs, among other toxic products. There was plenty of genius to go around. Too much perhaps.

Well OK, perhaps hiring geniuses doesn’t guarantee that your firm won’t go bankrupt or that the financial system won’t collapse. But what if it made it even more likely? What if some of the very geniuses that have been involved with financial failures in the past and are now the authorities on what exactly went wrong and what needs to be done, or avoided, to prevent future crises, are in fact drawing the wrong, potentially dangerous conclusions?

Let’s focus this discussion on the observations of a rather clever gentleman getting much press of late, Mr Jim Rickards, former general counsel to LTCM. In a recent interview with Kate Welling, he explains what he believes are perhaps the key reasons why the financial industry so badly miscalculated the risks it was taking going into the recent crisis:

As general counsel of LTCM, I negotiated the bailout which averted an even greater disaster at that point. What strikes me now, looking back, is how nothing was changed; no lessons were applied. Even though the lessons were obvious, in 1998. LTCM used fatally flawed VAR risk models. LTCM used too much leverage.3

These "VAR [Value at Risk] risk models" to which Mr Rickards refers are models which assume that financial asset price movements are normally distributed, that is, they follow a bell-shaped curve under which one standard deviation from the mean encompasses roughly two-thirds of all outcomes and by the time you have moved three standard deviations away you capture some 99% of all outcomes. That leaves the 1%, which is known in the industry as your “once in a century” event—so unlikely that, for practical business purposes there is little if any reason to worry about it. Indeed, the original Black-Scholes option pricing model, developed in the 1970s and for which the Nobel Prize in Economics was awarded in 1997, assumes a normal distribution. Although subsequently modified in various ways, option pricing models in use today still explicitly assume the normality—bell-curve distribution—of returns.

Mr Rickards is quite right that VAR is a “fatally flawed” concept. There is overwhelming evidence that financial price returns are not normally distributed but rather follow what is known in physics as a “power curve” distribution. Mr Rickard describes this as:

...a different kind of degree distribution. Any degree distribution is simply a plotting of the frequency of an event relative to the severity of the event... A power curve, one of the most common degree distributions in nature, which accurately describes many phenomena, has fewer low impact events than the bell curve but has far more high impact events...

A power curve says that events of any size can happen and that extreme events happen more frequently than the bell curve suggests. This corresponds to the market behaviour we have seen in such extreme events as the crash of 1987, LTCM’s collapse, the dot.com bubble’s bursting in 2000, the housing collapse in 2007—you get the idea. Statistically, these events should happen once every 1,000 years or so in a bell curve distribution—but are expected much more frequently in a power curve distribution. In short, a power curve describes market reality, while a bell curve does not...

Bell curve distributions in this context describe continuous phenomena and power laws describe discontinuous but regular phenomena.

Now we notice here two things: First, Mr Rickards is a seriously intelligent fellow with significant direct market experience and superior statistical knowledge. Second, and far more subtle but hugely important, we see that the financial industry as a whole has chosen to embrace VAR models, notwithstanding overwhelming evidence that they dramatically underestimate risk. If the financial world is populated by geniuses, what possible explanation could there be for that? Well he has an explanation:

[T]he history of science is filled with false paradigms that gained followers to the detriment of better science. People really did believe the sun revolved around the earth for 2,000 years and mathematicians had the equations to prove it... In effect, once an intellectual concept attracts a critical mass of supporters, it becomes entrenched...

I don’t know whether it was denial or inertia or because people got so wedded to the elegance of the mathematics they’d done that they hated to leave all that work behind... In other words, Wall Street decided that the wrong map is better than no map at all—as long as the maths are elegant. And that led to calling extreme events a sort of special case, a “fat tail,” which just meant they were happening more frequently than a bell curve would indicate.

Perhaps that’s it. But no, that’s not all. Mr Rickards goes one step farther which, given the huge rise in proprietary trading activities in recent decades, rings true:

[A]nother reason the Street was loath to throw out the whole notion of normally distributed risk, and tried to salvage it instead by putting a fat tail on it, is that the alternative, a power curve, just didn’t look that palatable to most practitioners and so comparatively little work has been done in applying power curves to financial markets...

The thing is, power curves don’t have a lot of predictive value. Since most financial researchers approach the field precisely to gain a trading edge, once they discover power curves aren’t much use there, they move on...

Good insight. Probably spot on. The consequences, as we know, have been devastating. Mr Rickards uses the severity yet unpredictability of earthquakes as an excellent analogy for financial crises and for what he believes should be done to avoid them in future:

We know that 8.0 earthquakes are possible and we build cities accordingly, even if we cannot know when the big one will strike. Likewise, we can use power curve analysis to make our financial system more robust even if we cannot predict financial earthquakes. And one of its lessons is that as you increase the scale of the system, the risk of a mega-earthquake goes up exponentially...

Unfortunately, this is not something that Wall Street or Washington currently comprehend.

Perhaps they don’t. But we’re not easily convinced of Wall Street’s ignorance in this matter. We’ll explain why in a moment. First allow Mr Rickards to continue with his explanation:

I’ve always thought the problem was that, although Wall Street was very active in hiring a lot of PhDs—astrophysicists, applied mathematicians and others with very good quantitative theoretical skills, it didn’t let them use their heads. What happened was that their Wall Street managers said, “Look, here’s how the financial world works and we want you to model it and code it and develop it and write these equations and programs.” And so they did... [I]nstead of telling them what to do, they should have listened.

Now why is that, do you think? As indicated above, we have an idea. Those Wall Street managers telling their quants what techniques to use were clever enough to understand that, were they to employ models based on power-curve distributions, it would not make prop trading any more profitable, as such models lack predictive power. But it would dramatically increase their cost of capital, as their capital bases would need to be large enough to insure against power-curve-implied “earthquakes”. Capital would need to increase and balance sheet leverage decrease exponentially alongside any growth in proprietary trading operations. How convenient and coincidental that Wall Street execs collectively created a VAR-based risk management culture at every single major trading firm, without exception, notwithstanding the overwhelming historical evidence that VAR is “fatally flawed”!

Perhaps Mr Rickards is just being polite. We have no such compunctions when it comes to entertaining ideas of possible conflicts of interest between Wall Street executives and their firms’ shareholders. In our view, the evidence may be circumstantial but it is clear. It was never in Wall Street’s interest to seriously consider replacing VAR-based with power-curve-based risk management because it would have raised the cost of capital, thereby curtailing profits, salaries and bonuses.

But wait a minute: Are we implying that Wall Street execs were willing to risk the bankruptcy of their own firms and even the collapse of the entire financial system by deliberately employing far too much leverage? Yes, we are. Remember, these are smart guys. Perhaps as smart as Newton. Perhaps as smart as Mr Rickards. Perhaps smarter still: So smart that they took a good look back at post WWII financial market history and saw that in every single instance in which the threat of systemic failure arose, policymakers intervened with progressively greater assistance. And, in every instance, the policy reaction has proven in retrospect to be disproportionate to the crisis and the moral hazard implicit in the system has grown. Indeed, it could be argued that the regulators have made the financial world safe for VAR-based risk models. If the power-curve distribution does indeed obtain, then given that the too-big-to-fail firms are now even larger than they were prior to the post-Lehman bailout, an even larger financial crisis, with an even larger bailout price tag, lurks in the not-so-distant future.

***

Whether or not he believes that Wall Street executives deliberately chose to ignore the implications of the power-curve distribution or were simply blissfully unaware, Mr Rickards has specific recommendations for how to avoid another major financial crisis:

[O]nce we understand the structure and vulnerability of the financial system in this way, some solutions and policy recommendations become obvious...

They fall into three categories: limiting scale, controlling cascades and securing informational advantage...

I certainly would favour the Volcker Rule and I would favour bringing back something like Glass-Steagall. And I’d favour imposing stricter capital ratios on banks and brokers.

What these recommendations collectively would do is to give substantially greater power to regulators to determine how Wall Street is run. But stop right there. Is this realistic? Who, exactly, is going to determine how to “limit scale”? How can we have any confidence that such decisions will not be highly politicised? By controlling cascades, are regulators not providing an implicit subsidy for excessive risk taking? Mr Rickards might counter that his proposed stricter capital ratios would limit such risk-taking, but once again, can we be at all confident that such capital ratios will be set in a sensible, objective, non-politicised way, given the history of chronic failures on the part of regulators to effectively carry out their mandates?

Our concerns with a purely regulatory-based solution come down to the following: Is Mr Rickards really prepared to place his faith in the regulators who enabled the S&Ls to embark on their fateful 1980s lending binge; who failed to see the dotcom bubble but then wasted no time slashing rates when the market crashed; who denied that there was a housing bubble even as they were claiming that the nascent subprime crisis was “contained”; who were supposedly overseeing Fannie and Freddie in the years prior to bailing them out completely; who repeatedly missed (or chose not to hear) Madoff warnings; who glossed over Lehman 105 repo transactions; who bailed out AIG CDS at par even though such contracts were trading at a huge discount in the market?

To be fair, Mr Rickards is in good company. There are numerous policymakers and financial commentators who appear not to have learned the rather obvious lesson that the US financial regulatory regime not only repeatedly fails, but fails so completely, consistently and predictably that Wall Street has made a highly profitable business out of being bailed out. As Sir Isaac Newton might ask, have these folks fumbling for a regulatory-based solution to Wall Street excess thought to apply the scientific method properly, isolating key assumptions and controlling for all factors? If they did, they might see the disturbingly consistent pattern right before their eyes.

We agree wholeheartedly with Mr Rickards that VAR is a flawed concept and that a power-curve approach to risk management would be a welcome step in the right direction. But with all due respect, we are horrified at the prospect that the dysfunctional US financial regulatory system would be tasked with such an important initiative.

If more such “misregulation” is not the answer, then what is? Our solution is simple: Throw Wall Street to the wolves. Congress should pass a law making it illegal for the government or any agency thereof, including the Fed, to provide any form of direct financial assistance whatsoever, under any circumstances, to the non-depositor sources of funding for the financial system.

How would financial markets respond? Presumably, absent any explicit or implied guarantees, the share prices of weak financial firms would decline, perhaps to levels implying a high risk of insolvency. The weakest institutions would probably also find that their bonds were trading at a large discount and would find it difficult, if not impossible, to refinance at attractive rates. They would be forced to shrink their balance sheets, if not immediately, then gradually over time. Larger (uninsured) depositors would begin to withdraw funds from those institutions deemed at growing risk of failure and place them in stronger institutions. They would also most probably spread deposits around, seeking greater diversification of risk. In general, capital would flow from weak to strong financial institutions, exactly what is needed to avoid a repeat of 2008.4

Shareholders, now aware that assistance would not be forthcoming in a crisis, would demand that financial executives not only increase their respective firms’ capital cushions but also devote more resources to and provide greater transparency of risk-management. For institutions taking material proprietary risk in trading or investment banking, a general move back to a partnership model in which executive wealth is tied to the stability and longer-term survival of the firm and in which conflicts of interest with shareholders and bondholders are minimised, would probably take place. Specifically, shareholders would probably demand that risk-management replace flawed VAR-based methodologies with those based on a power-curve distribution. What Mr Rickards thinks should be done by chronically incompetent regulators would almost certainly be done in short order by increasingly competent, if imperfect, financial executives, in response to shareholder pressure.

Mistakes would still be made. Geniuses aren’t perfect. But absent a homogenous VAR-based risk-management culture, the risk of systemic failure would be all but eliminated. If any firm grew to the point of posing a systemic risk, the cost of capital for the entire system would rise accordingly, constraining growth and re-allocating resources to less risky nonfinancial business sectors.

We believe we know why financial genius fails. The answer is surprisingly simple really: Because failure pays so much better than success. Only when action is taken to ensure that success pays better than failure, will financial crises threatening the health of the entire economy become a thing of the past.

The Amphora Liquid Value Index (through March 2010)

Resources:

1 Several triggers for “Black Monday” have been proposed in a number of papers. One relatively recent study was prepared by Federal Reserve staff and listed rising global interest rates, a weaker dollar and rising US trade deficit as potential fundamental, macroeconomic causes and a proposed corporate tax change, listed options expiry and large redemptions from a prominent mutual fund group as potential immediate triggers. See A Brief History of the 1987 Stock Market Crash with a Discussion of the Federal Reserve Response by Mark Carlson, Federal Reserve Board of Governors Finance and Economic Discussion Series, 2006. https://www.federalreserve.gov/pubs/feds/2007/200713/200713pap.pdf

2 A reasonably complete timeline of the key events leading up to the S&L crisis is provided by the FDIC at https://www.fdic.gov/bank/historical/s&l/

3 This quote, and all subsequent quotes from Mr Rickards, are taken from a fascinating interview by Kathryn Welling of Welling@Weeden, Vol 12/4, 26 Feb 2010. We take this opportunity to thank Welling@Weeden for permission to use these quotes.

4 There are those who would argue that government-funded deposit insurance itself is a form of moral hazard. Rather than enter into such a discussion, we find it simpler to emphasize that, were financial shareholders and bondholders to act as if there was no implied bailout for financial firms, they would demand more sensible risk-management, quite possibly along the lines of what Mr Rickards recommends. Doing away with the FDIC is probably not necessary in this regard.

DISCLAIMER: The information, tools and material presented herein are provided for informational purposes only and are not to be used or considered as an offer or a solicitation to sell or an offer or solicitation to buy or subscribe for securities, investment products or other financial instruments. All express or implied warranties or representations are excluded to the fullest extent permissible by law. Nothing in this report shall be deemed to constitute financial or other professional advice in any way, and under no circumstances shall we be liable for any direct or indirect losses, costs or expenses nor for any loss of profit that results from the content of this report or any material in it or website links or references embedded within it. This report is produced by us in the United Kingdom and we make no representation that any material contained in this report is appropriate for any other jurisdiction. These terms are governed by the laws of England and Wales and you agree that the English courts shall have exclusive jurisdiction in any dispute.