The current downtrend in natural gas has become epic, with the discount to petroleum huge and growing. With crude oil breaking $100 and the nuclear disaster in Japan likely to increase demand for fossil fuel energy, it is tempting to think that natural gas in the US has found a floor. Unfortunately, the story is a bit more complicated.

You don’t need training in economics to understand that a cleaner fuel that sells for less per unit of energy should be preferable. To see the price of this fuel getting cheaper and cheaper while its competitors get more expensive offends the sensibilities and creates a cognitive dissonance for many of us. However, such is the result of inflexibility of fuel inputs, particularly liquid fuels in the modern world. Despite being clearly inefficient in an economic systems sense, low natural gas prices have demonstrated a persistence that few of us expected.

The underlying reason for this is that the US natural gas market has existed as its own little island for much of the past few years, interacting very little with world natural gas markets and other domestic energy types. There are many reasons for this lack of interaction.

Ready to Party, but Got no Wheels

To a large extent, this island effect can be attributed to the lack of elasticity in the personal transportation sector. We run around paying $4 a gallon for gasoline – meanwhile drivers of Compressed Natural Gas (CNG) cars in Salt Lake City pay just over a dollar for the equivalent of a gallon of gas and drivers in southern California pay around $2. While that sounds pretty compelling, there are a couple of downsides as well: there are fewer CNG stations (and none in many parts of the country) and even fewer vehicle choices (the only private car I’ve seen is a Honda Civic CNG). If there were many models of CNG cars and trucks available in the US, and ubiquitous fueling stations, I’m pretty certain CNG demand would skyrocket. The fact that those stations and models don’t exist however is a testament to how cautious the energy and car industries are to make tectonic shifts in strategy.

Hotel California

Another factor limiting the substitution of US natural gas into other energy markets is that liquefied natural gas (LNG) is a one-way street for the US – LNG can “check in any time it likes, but it can’t ever leave.” This is because the US currently only has regasification plants, meaning we can import LNG but cannot export it. Plans to build liquefaction plants are still on the drawing board and the soonest estimate I’ve seen for completion would be 2015. Of the roughly 1 BCF a day that we import, nearly 100% of it is in long term contracts and would have left our market and gone somewhere else long ago if it could have. Therefore world demand for LNG does not have a direct mechanism to affect the US natural gas market with the current disparity in prices.

Displace Crude Demand? You’re Dreaming!

The previous link with crude oil and petroleum products (dual use plants that could use petroleum or natural gas) was broken years ago, so there is nothing that remarkable about the crude/natural gas BTU differential growing ever wider, except that it increases the already sizable incentive to find ways to shift demand to natural gas. One can still imagine the odd household that realizes they can save a bazillion dollars a year by switching their heating fuel from heating oil to natural gas, but in most markets where natural gas is available the switch has already been made.

If you haven’t been convinced of a game changer in natural gas until now, this should convince you: the new game in town for natural gas is electric generation replacing… wait for it…coal! It would have been hard to imagine natural gas competing with coal in the middle of last decade, but in 2009 coal to gas switching resulted in an additional burn of 1100 BCF, and the 2010 estimate is 700 BCF of substitution!

This coal to gas substitution could be a mechanism by which the US natural gas becomes linked to the world LNG market (and world energy markets more generally.) Coal demand in Europe, for example, competes with world LNG prices which are currently close to $10/BCF. If coal demand from outside the US raises the price of coal in the US, this would in turn make coal to gas substitution within the US more attractive. However, even this pass-through in prices depends on multiple steps and substitutions to occur.

Current Coordinates – Oversupplied

The most shocking thing for many natural gas market participants is that during the past 18 months, a period with pronounced oversupply, we have had 3 consecutive very bullish weather seasons – a cold winter, a very hot summer, and a very cold winter. Had any one of these seasons been neutral or bearish, it would have given us a much better picture of what price is necessary to reduce new shale supply. We may be given yet another chance, as many of the dynamics that created cheap gas are still in play – land leasing agreements, joint ventures, unfinished wells, and byproduct gas.

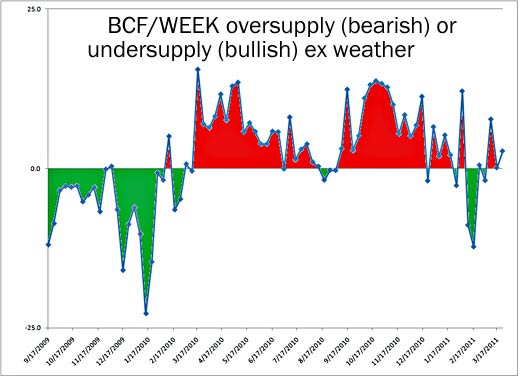

The chart below is my back of the napkin estimation of supply and demand, after backing out the effects of weather. As can be seen, we have been “oversupplied” for 12 months straight, anywhere from 5 to 15/BCF a week. The only time the model indicates we were undersupplied in the past 12 months was during the freeze-offs in February when 5 BCF/day of production were offline due to cold temps in Texas and Oklahoma.

Figure 1: Supply and demand after accounting for changes in weather related demand. Red indicates oversupply, and green indicates undersupply.

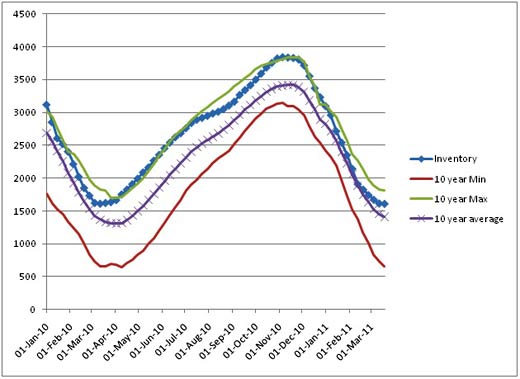

Moving on to inventory levels, the chart below shows current inventory relative to 10 year max, min, and average. While we are only slightly above 5 year averages, we are still significantly above 10 year averages for the end of the heating season. Again, imagine where inventory levels would be if we hadn’t just had the coldest winter in 10 years!

Figure 2: Natural Gas Inventory in the US. Inventory has been above the 10 year average for more than 2 years now… despite 3 consecutive bullish weather seasons.

Other Headwinds to a Long Natural Gas Position

Probably the greatest headwind to investing long in a natural gas position, however, has little to do with the aforementioned supply/demand issues: it has to do with contango and the so-called term structure of different natural gas futures contracts. You see, if you are of the opinion that natural gas prices will go up over time, you have lots of company. So much company in fact, that future contract prices are already priced at a level significantly above current prices. The problem with this, from an investment perspective is that prices have to go up in addition to the level already priced into future contracts to make money.

Figure 3: The natural gas strip shows the current price of all natural gas futures contracts out to 2024. December 2014, as an example, is currently priced at /BCF. The prompt contract (whichever contract is first in line) has performed poorly over the past few years as it converges to spot price month after month.

Additionally, if you are using an ETF such as UNG, the problem can be compounded by movements in the prompt contract. To visualize the extreme of this problem, imagine the price going from to once a month, and then repeating month after month. You would lose 75% of your investment each month, and it wouldn’t be long before you had essentially nothing. This is an exaggeration on the results that vehicles like UNG have provided, but performance has been bad enough that it reminds me of the old investment joke:

Q: What do you call an investment that is down 90%?

A: An investment that was down 80% and then dropped an additional 50%.

Figure 4: UNG June 2008 to present. Despite horrendous losses in UNG due in large part to the issue of contango, “community sentiment” on Marketwatch.com remains stubbornly bullish for this ETF.

A Bright Future

The last thing you should think is that I am a natural gas permabear. I’ve “enjoyed” being long natural gas over the years as much as being short. Furthermore, I think that conceptually, natural gas offers the US a great reprieve from an otherwise crushing energy dilemma brought around by peak oil or peak cheap oil (depending on your preference). However much one thinks natural gas should be more expensive, using that opinion as a basis for investment decisions might not be the most profitable response to the situation. Finding a way to use natural gas as a primary fuel might be a better alternative. Finding out if you can switch heating or utilities to natural gas, determining whether buying a CNG car is a viable alternative for you, and encouraging our Congress critters to make systemic changes that encourage natural gas use are all actions that are potentially much better at helping the country and the pocketbook.

Finally, there will come a time, whether in one month or 10 years, when natural gas has a compelling bullish story. However, that time will most likely be accompanied by signposts such as:

- Backwardation instead of contango in the natural gas price strip.

- Inventory levels below 5 and 10 year averages for a sustained period.

- Bullish supply and demand disposition ex weather.

- Bearish summer or winter weather accompanied by flat or rising prices.

- Overzealous claims and focus by the mass media to the effect that natural gas will solve all our energy problems.

- Significant changes in natural gas infrastructure aimed at increasing future demand for natural gas.

- A negative inflection in shale production, resulting either from regulations, lack of drilling capacity, or natural decline.

Until that time, enjoy using natural gas, but use caution investing in it.

P.S. I can’t help but think that articles such as this could “mark the bottom,” that a systemic shift has already occurred in the gas market behind the scenes, and articles like this represent the thinking associated with a peak bearish sentiment. However, I decided to publish the article in spite of that risk.