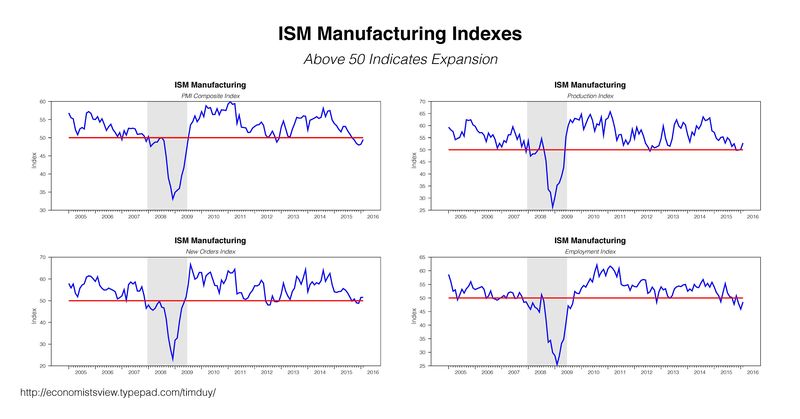

The beleaguered manufacturing sector saw an uptick in February, at least according to the ISM report:

This information builds on the stronger consumer spending and inflation numbers we saw last week. Not to mention solid auto sales for February. The news is sufficiently good that Torsten Sløk of Deutsche Bank argues (via Business Insider) that the Fed should raise rates:

Today we got more confirmation that the negative effects of dollar appreciation on the US economy are starting to fade, see the first chart below. Specifically, we have in recent months seen a solid turnaround in the employment data for the manufacturing sector and in the manufacturing ISM. Combined with the acceleration we are seeing in consumer spending and inflation I would argue that if the Fed is truly data dependent then they should be raising rates at their next meeting...

I don't think the Fed will raise in March, nor do I think they should raise in March. I think the financial markets signaled fairly clear that further tightening now would be a mistake. The Fed would be wise to heed that call.

Read: Russell Napier Forecasts Negative Rates in the US as Deflationary Pressures Spread

And, if New York Federal Reserve President William Dudley is any indication, they will heed that call. Indeed, he goes even further than me. Whereas yesterday I raised the possibility of a "hawkish pause" at the March meeting where the Fed revives the balance of risks with an upside bias, he opens the door to the opposite.

First, note that Dudley appears unmoved by the uptick in core inflation:

Turning to the outlook for inflation, headline inflation on a year-over-year basis has begun to rise as the sharp falls in energy prices in late 2014 and early 2015 are removed from the calculations. However, inflation still remains well below the Federal Reserve’s 2 percent objective. As the FOMC has noted in its statements, this continued low inflation is partly due to recent further declines in energy prices and ongoing impacts of a stronger dollar on non-energy import prices. Although energy prices will eventually stop falling and the dollar will stop appreciating, these factors appear to have had a more persistent depressing influence on inflation than previously anticipated.

This is actually quite dovish. If core inflation is a good signal for the direction of overall inflation, then the latter will leap sharply when the "transitory" impacts fades. This suggests to me that the forecast of a gradual return to target is almost certainly wrong. When (and if) inflation turns, it will turn quickly. Dudley is discounting that possibility.

I suspect he is discounting inflation concerns because he is focused on inflation expectations:

This continued period of low headline inflation is a concern, in part, because it could lead to significantly lower inflation expectations. If this drop in inflation expectations were to occur, it would, in turn, tend to depress future inflation. Evidence on the inflation expectations front suggests some cause for concern...

...With respect to the market-based measures, there are some reasons to discount the decline...Still, given the extent to which inflation compensation has fallen since mid-2014, I believe that it is prudent to consider the possibility that longer-term inflation expectations of market participants may have declined somewhat.

What I find more concerning is the decline in some household survey measures of longer-term inflation expectations....To date, these declines have not been sufficiently large for me to conclude that inflation expectations have become unanchored. However, these developments merit close scrutiny, as past experience shows that it is difficult to push inflation back up to the central bank’s objective if inflation expectations fall meaningfully below that objective. Japan’s experience is cautionary in this regard.

Asymmetric risk surrounds inflation expectations. Difficult to raise up, but easy to push down. Hence, it is important to guard against falling expectations. This is especially the case as he sees risks to the outlook as now tilted to the downside:

Now, putting these inputs and my judgment together, I see the uncertainties around my forecast to be greater than the typical levels of the past. This assessment reflects the divergent economic signals I highlighted earlier, and is consistent with the turbulence we have seen in global financial markets. At this moment, I judge that the balance of risks to my growth and inflation outlooks may be starting to tilt slightly to the downside. The recent tightening of financial market conditions could have a greater negative impact on the U.S. economy should this tightening prove persistent and the continuing decline in energy and commodity prices may signal greater and more persistent disinflationary pressures in the global economy than I currently anticipate. I am closely monitoring global economic and financial market developments to assess their implications for my outlook and the balance of risks.

Hence, Dudley is likely to stand as a bulwark against FOMC participants who think the Fed should hike in March and those who would like a more optimistic balance of risks. Moreover, this is a pretty clear signal of his expectations for March:

The federal funds rate is only one element of the broader set of financial conditions affecting the U.S. growth and inflation outlook. Tighter financial conditions abroad do spill back into the U.S. economy, and policymakers must take this into account in their assessment of appropriate monetary policy. Of course, this does not mean that we will let market volatility dictate our policy stance. There is no such a thing as a “Fed put.” What we care about is the country’s growth and inflation prospects, and we take financial market developments into consideration only to the extent that they affect the economic outlook.

In other words, when we don't hike in March, it's not because of a Fed "put" on the stock market. It is more accurately a Fed "put" on the economy. Financial market weakness signals tighter financial conditions, and to prevent those conditions from spilling into the rest of the economy, the Fed needs to respond with a more accommodative policy stance. The Fed then is not saving Wall Street. It is saving Main Street from Wall Street.

The upshot is that if the economy remains on firm ground (the "no recession" camp), inflation is heating up, and the Fed goes solidly dovish, we should see the yield curve steepen in the near term, at least until the Fed turns hawkish again. If we are really lucky, the secular stagnation story is wrong and the entire yield curve lifts up as the Fed chases higher rates. Then we could really imagine the "short treasuries" bet to be a no-brainer. If secular stagnation remains the order of the day, then the long end quits rising soon after the Fed sends out hawkish signals, setting the stage for a renewed flattening.

Don't miss: OECD's William White: In Terms of Debt, the Situation Is Way Worse than 2007

An interesting possibility is that in the back half of 2016, inflation pops above trend and one of the Fed's fears is realized. That fear is that they fall behind the curve and need to raise rates quickly to counteract rising inflation. They seem to think that they have no choice at that point but to murder the expansion. I disagree with that conclusion. I think they tend to forget about the long and variable lags of policy at the end of the cycle and consequently rush raising rates needlessly. In any event, how they respond to (potentially) higher inflation later this year will shape the 2017 and 2018 economic environment. So, obviously, it is something to keep an eye on.

Bottom Line: The Fed will take a pass on the March meeting. Whether the statement is dovish, neutral, hawkish is the key question. Dudley opens up the possibility of a not just a neutral statement, but a dovish one. My sense is that this is shaping up to be a very contentious meeting as participants struggle with the question of exactly which data are they dependent upon.