You are probably fully aware that the largest US bank, JP Morgan, had a more than noticeable derivatives loss that was announced a few weeks back. In fact, regulators seemed so taken aback that they had JP’s CEO, Jamie Dimon, appear before the Senate Banking Committee to explain. Only a week prior to the announced loss, Mr. Dimon conducted the first quarter earnings conference call for JP. As you’d guess, not a mention of a derivatives related problem. I can only infer that a) Mr. Dimon was not being completely truthful on the prior period earnings conference call, or b) Mr. Dimon, the management team and Board of Directors at JP really have no idea of the overall directional and individual position risk in JP’s derivatives book. It’s either one of the two. Fortunately, given that I have no reason to believe Mr. Dimon is untruthful, it’s probably the latter. Unfortunately, I’m not so sure that isn’t scarier than the former. Why? It just so happens JP Morgan is the largest holder of financial derivatives contracts…on planet Earth.

The wonderful world of financial derivatives is opaque at best, and completely non-transparent at worst. There is no disclosure of positions or risk posture in any company specific regulatory filings. The industry tells us non-disclosure is for competitive reasons and there is some merit to this argument. But even in light of the AIG 2008-2009 derivatives accident that precipitated the larger Wall Street bailout and now the JP Morgan loss measured in billions, regulators have simply turned a blind eye. Make no mistake about it, Goldman and Morgan Stanley would be distant memories, as would have a number of other leading US financial firms, had it not been for the Government bailout of the AIG derivatives debacle. Maybe a bit surprising, the most vocal advocate for derivatives non-disclosure was none other than Alan Greenspan over the last few decades. Of course this was just one of his many “accomplishments”.

Why should we care about all of this? I’ll be the first one to suggest that financial derivatives serve a very needed function in the greater domestic and global economy. At a very basic level as a simple example, farmers can use commodity derivatives to “hedge” or lock in price levels for their crops well in advance of actual harvest and sale. It allows them a certain degree of financial certainty from planting to harvest. Large corporate users of energy can hedge against higher energy costs over a certain period, again giving them a sense of operational cost certainty. The permutations on the theme in terms of derivatives serving a solid business purpose are almost endless. But practicality ends when derivatives are being used increasingly for speculation. It’s here where I personally believe the regulators are miles behind the financial markets. But the reason this is important to at least be aware of is magnitude of the existing derivatives complex and the clear examples of very large mistakes in recent years. In a minute, I’ll leave you with what are hopefully are two important questions of the moment for the domestic and global derivatives complex. Unfortunately, I have no answers for either question. Don’t worry, you don’t either.

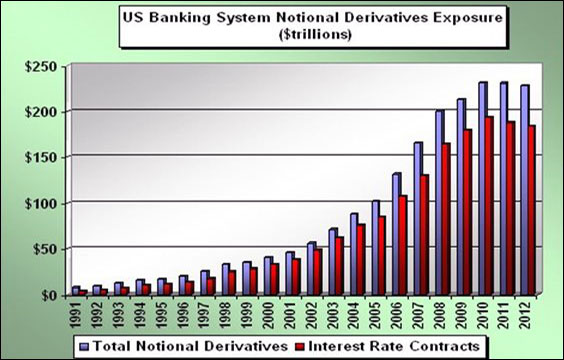

One of the very few places we see any actual disclosure of derivatives numbers is in the OCC (Office of the Comptroller of the Currency) quarterly derivatives report. I thought I’d quickly run through a number of facts which I personally believe most folks are unaware. It’s also a reason that I have a very hard time investing in many financial stocks currently when I cannot see what I believe is very meaningful risk exposure on balance sheets. Let’s face it, if the CEO of the largest US bank could not see a large derivatives problem coming, then how are shareholders ever expected to anticipate such an occurrence? The OCC looks only at the US banking system in their report. Important in that the large US banks are some of the largest holders of derivatives worldwide. The second largest holders? The European banks. Feeling comforted? The chart below looks at total US banking system derivatives exposure really since the inception of the broader derivatives markets in the late 1980’s. From about $10 trillion in notional exposure, US banking system derivatives holdings have grown to over $225 trillion as of the first quarter of this year. This is exactly the magnitude I believe is so important.

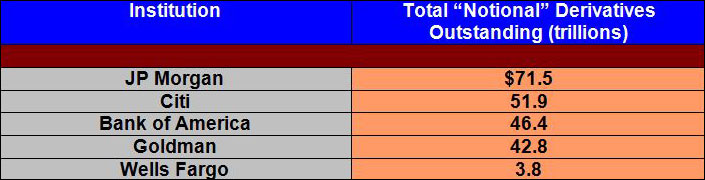

Of course from here the story gets a bit more interesting. 97% of total US Banking system derivatives exposure can be found in five institutions. The table below lists those institutions alongside their notional derivatives exposure as the first quarter of this year concluded.

A very quick, but needed, tangent. We first need to remember that derivatives are very highly leveraged vehicles as transactions are completed via use of margin. This is far too simplistic, but maybe an entity controls a dollar of exposure, but posts cash of a nickel to control this one dollar of a derivatives contract. Admittedly, numbers like .5 trillion in exposure at JP Morgan look shocking. It’s not that JP Morgan has trillion at actual risk. But let’s face it, even fractions of trillion can mean billions of real nominal dollar risk exposure, as exactly was the case for JP just a few weeks back. And as you know, the final derivatives loss for JP is far from having been officially tallied.

Do you think the big US banks were too big too fail back in 2007? Think again. At year-end 2007 the big US banks had 5 trillion in notional derivatives exposure. At the end of the first quarter of this year that number is now 8 trillion, an increase of close to 40%! The large banks may have shrunk their lending into the real economy, but their profitable and often speculative derivatives business has kept growing like weeds. By inference, so has their risk exposure.

Again, there are so few spots of disclosure regarding derivatives that I thought it important to at least highlight what few facts are available publicly. I’ll leave you with two issues in the derivatives world I believe applicable and important to the markets of today. They are questions to which I have no answers. But I believe they are important to incorporate into risk management in this ever intertwined world in which we find ourselves.

Most banks enter into derivatives contracts as an accommodation to their clients. Of course they are trying to earn a profit in this exercise. Their clients want and need to offset a certain risk and so the banks take the “other side” of this risk. That may be interest rate risk, risk of a movement in commodity prices, etc. But once the client accommodation transaction is complete, the bank now finds itself with a new financial risk that is the derivatives contract they have just written. What do the banks do to offset this newfound risk? They turn right around and enter into yet another derivatives contract with a “counter party” to offset the risk they have just accepted on behalf of their original client. The client of the bank essentially “hedged” a risk important to them. The bank turns around and “hedges” the risk they took on for their client. In the banking world this offset or hedging of derivatives risk is called “bilateral netting”. The following shows us the history of the US banking system in terms of how much derivatives risk they have ”laid off” (bi-laterally netted) over time to others.

You’ll be happy to know that as of the first quarter of this year, the US banking system tells us it has offset 91.8% of its derivatives risk exposure. You’ll be less than happy to know that we have absolutely no idea just who these “counter parties” to the US banks may be in this hedge as there is zero disclosure. When AIG hit the wall in 2008, the public could never have known what was to come, as there was no disclosure so this risk could have been anticipated. The key point is this. With $227 trillion of notional derivatives exposure, there are very, very few players on planet Earth who would be large enough to offset US banking system derivatives risk. And without question, one of those “players” by sheer process of numbers elimination is the European banking system. You remember, the same one that seems to be melting down each day in the news. Critical issue number one, to what extent are Euro banks derivatives counter parties to the large US banks? Will a number of these be nationalized before this cycle is over and will the new counter party be a Euro area sovereign? Will the sovereigns stand ready to honor these obligations? And the good news of the moment is? No one has any idea.

Yes, the real economy of Europe is being impacted negatively by European bank and sovereign debt (government debt) stress. But how is this credit market stress impacting US bank derivatives counter party risk with European banks? We have no idea at all as we’re completely in the dark.

The second very meaningful issue of the moment is that the mountain of leverage that is the global derivatives markets sits atop what is assumed to be sound collateral. In most cases government debt/repo vehicles, which is assumed to be risk free, forms the bulk of this collateral, but again there is no disclosure. Unfortunately in the case of AIG a number of years back, we woke up one day to find that there was a massive shortage of collateral when AIG’s derivatives bets went bad. The regulators never knew. AIG’s derivatives counter parties never knew, and of course AIG shareholders were the last to find out.

Fast forward to the present. The important issue of the moment is that European collateral is “shrinking” almost by the day. As interest rates go higher in Spain, Italy, Portugal, etc., the value of their government debt falls in price – the collateral, if you will, shrinks. As a very macro comment, the KEY issue in European credit markets is that the large financial players as well as sovereigns are running out of collateral. Will this ultimately mean anything for or have repercussions with US financial institutions intertwined in derivatives contracts with European financial firms? Again, with a surfeit of disclosure, we only wish we knew. It remains the key reason I personally have a very hard time committing capital to balance sheets (financial stocks) I can only partially assess for risk. Quite simply, what I do not know, and neither does anyone else, is if there are yet further Dimon’s in the rough on the financial sector derivatives playing field.