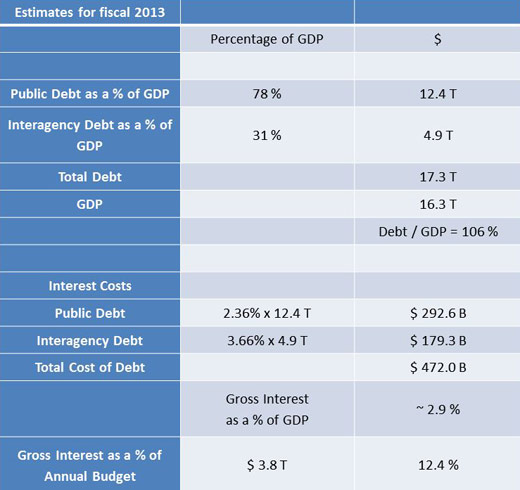

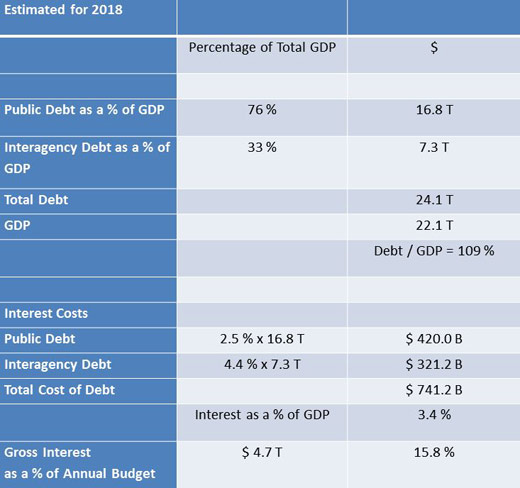

Assuming no unusual economic event occurs during the last 6 months of the federal fiscal year (ending September 30, 2013), American GDP for that period should be in the range of ~ 16.3 trillion. If so, then the United States will end its fiscal year with a debt to GDP (Gross Domestic Product) ratio of 106%. That means for every $1.00 of GDP, the Federal government owes someone one dollar and six cents. About 78% of this debt to GDP ratio will be in the form of public debt: money that has been borrowed from pension funds, foreign banks, insurance companies, individuals, and so on. Buyers receive notes, bonds and other financial instruments that promise to repay the face value of the paper they purchase plus interest. Interest on this paper is projected to have an average year-end rate of 2.36%. Gross interest costs are estimated to be ~ $293 billion. (Note 1)

Gross Federal Debt also includes interagency (intergovernmental) debt. For the full fiscal year, another 31% of this debt to GDP ratio was in the form of money that has been borrowed from other federal agencies. These securities, issued by the Treasury, include paper issued to government trust funds, revolving funds, special funds, and the Federal Financing Bank. Social Security is the largest Trust fund and holds over 50% of the Treasury’s interagency paper. Other large creditors that own Federal Government debt include the Civil Service Retirement and Disability Fund, the Medicare Trust Fund, and the Military Retirement Trust Fund. Treasury gives these agencies an electronic IOU that acknowledges the existence of the debt. Booked (but not paid) interest costs for the 2013 fiscal year are estimated to be about $179.3 billion.

Public debt should end fiscal 2013 at ~ $12.4 trillion, interagency (intergovernmental) debt is estimated at ~ $4.9 trillion, and total debt is projected to be ~ $17.3 trillion. The 2013 fiscal year federal budget is $3.8 trillion. For fiscal 2013, total accrued or paid gross interest costs are estimated to be about 12.4% of the federal budget, and about 2.9% of GDP.

With the exception of maturing paper, and demands for funds received by Federal agencies, there is no provision in the 2013 budget to repay any prior debt. The total debt outstanding, including accumulated interest, just keeps growing larger each year.

Despite the common belief that China holds an enormous portion of U.S. debt, two-thirds of the treasury’s bankroll currently comes from the Social Security Trust Fund, pensions for public-sector workers, pensions for military personnel and other retirees, and American investors. China, with less than 8 percent of the U.S. government’s paper, is among several nations that invest in treasury securities. As of March 2013, the Federal Reserve was holding .79 trillion in U.S. Treasury securities. On a net basis, it increased its holdings of treasury securities by .9 billion in calendar 2012. The Federal Reserve is required to send its net profits to the treasury, and was able to pay .9 billion in profits to the treasury in 2012.

For the full fiscal year 2013 budget, gross treasury interest costs are projected to be 2 billion. These interest costs are paid in cash, IOUs, and electronic transfers to its creditors. But treasury does not have to raise 2 billion. This amount is offset by funds received from on and off budget funds, as well as other interest and income sources. Projected net debt interest costs, which are included in the federal government’s annual fiscal budget, will be approximately 7.7 billion.

But why, we ask, is all this accumulation of debt so important? To answer this question, let’s go out five years and construct a scenario for 2018. If GDP is .1 trillion, and accumulated debt has increased to .1 trillion (both reasonable expectations), then America will have a debt to GDP ratio of 109%. About 76% of this debt to GDP ratio will be in the form of public debt. The remaining 33% will be in the form of debt owed to agencies and Trust Funds. Normalized interest costs on America’s federal debt will have increased by 80% to 1.2 billion. If the federal budget is (as proposed) .7 trillion, then interest costs will increase to 15.8% of the annual budget. (Note 1)

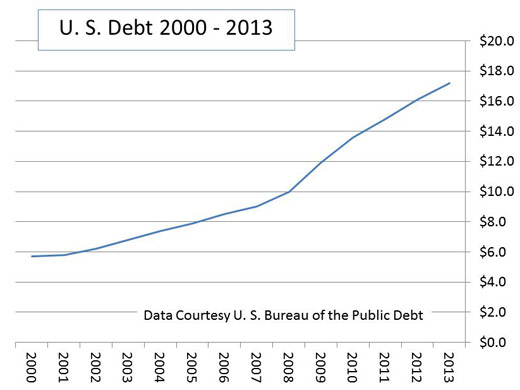

For those of you who like their data in pictures, I have included a graph of America’s debt from 2000 – 2013. The data comes to us courtesy of the U. S. Bureau of the Public Debt.

It is also useful to visualize the annual gross cost of America’s federal debt for 2013 and 2018.

But there are two problems.

In my opinion, by 2018 Social Security and Medicare (and perhaps some other trust funds) will no longer be net buyers of treasury securities. They are going to want some portion of their money back in order to fund projected retirement benefits. If so, the treasury interest income statement will look something like this.

According to this scenario, net treasury interest costs will have increased by 124% to 5.8 billion. These increased interest costs will have to be included in the projected federal budget of .7 trillion, forcing either a reduction of federal spending or an increase in the budget. America will either have to raise taxes or borrow more money just to pay the interest on the federal debt. Here is a graph of these estimates.

This brings us to the second problem. What if we want to pay down the federal debt? Could we? What happens if we just try to pay off the debt that will exist at the end of fiscal 2018 over a period of 20 years? Dividing $ 24.1 Trillion by 20 years means we would pay off $ 1.2 T of America’s debt each year. The federal budget for 2018 would have to be increased by at least 25% to .9 trillion, and ~ 30% of the federal budget would be allocated to servicing America’s federal debt. (Note 1)

Could America pay off its debt? A graph says it all.

It’s not hard to visualize the scope of America’s debt challenge. Unfortunately, the increased debt service, including the payment of principle and interest, would be a politically unacceptable burden on the budget. In addition, all too many people in Washington - for political reasons - do not believe any meaningful debt reduction is necessary. Consider the plausible solutions:

- Use austerity measures including a reduction of Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid and other health and retirement benefits to hold the line on further indebtedness.

- Use draconian austerity measures, including a wealth tax on bank accounts, to save the financial system.

- Increase sales and income taxes.

- Shift an increasing share of health care costs to the American worker.

- Shift more federal spending to State government budgets.

- Increase the rate of inflation by adjusting interest rates.

- Print money (also inflationary).

- Default on selected blocks of treasury debt

- Take a much longer time to pay off the debt

- Use trade and/or currency measures to enhance domestic economic growth.

- Increase tax revenues by encouraging the growth of the private sector.

- All or some of the above.

But most of these solutions are not politically expedient. America has accumulated an excessive load of debt, is stuck with costly interest payments, and has become vulnerable to the availability of capital (including money created by the Federal Reserve). It is also worth noting these debt estimates do not include a massive off balance sheet accumulation of unfunded obligations for which the America people are legally responsible. There is only one rational conclusion: America has been led into a debt trap from which there is no politically expedient escape. Given the size of the debt burden and Washington’s attitude, a full repayment of America’s existing debt obligations is highly unlikely. In other words:

America will never “pay off” its load of federal debt.

This raises an interesting question. If there is no attempt to control the amount of debt on America’s balance sheet, at what point does America become a bad credit risk? And what would happen next?

The election of 2016 should be lively. Someone will point out America’s political elite have buried our children in a mountain of unmanageable debt. Someone will point out Washington has demolished the economy. Someone will claim federal policies have made Wall Street rich. Someone will point out our political system isn’t working.

Someone will propose a radical solution.

Ron

Notes:

Note 1: Data gleaned from Federal Reserve, Treasury, GAO and CBO sources. Estimates are based on a risk adjusted analysis of publically available federal data. The objective of this essay is to provide the reader with a simple and concise explanation of America’s budget debt challenges. The debt costs discussed in the essay do NOT include planned (or unplanned) additions to Federal debt obligations, nor do they include unfunded government obligations (health care, Social Security, welfare, pensions, etc.), or State and Local debt.

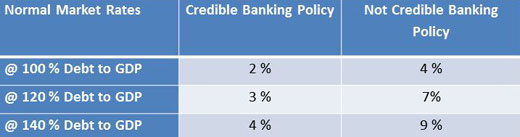

Note 2: Other interest rate assumptions would give a range of interest costs from 0 - 0 billion. The Social Security Trust Fund assumes it will get a minimum of 3.5% interest per year on the treasury paper held by the fund. Other agencies have similar expectations. As a reference, here is the theoretical range of interest rates at various debt to GDP ratios.

Note 3: Trust Fund Management Program.

The Secretary of the U.S. Treasury is designated by law as the managing trustee for eighteen of the approximately two hundred thirty Federal Investment Funds. With over .5 Trillion in assets, the Treasury-managed Investment Funds are the majority of the largest Trust Funds in the Federal Government. They receive Social Security, Medicare, excise and employment taxes---all collected by Treasury---as well as premiums, fines, penalties and other designated monies collected by the agencies that administer the programs for which these Trust Funds exist.

The Bureau of the Public Debt is delegated the responsibility for administering these eighteen Funds. For each of these Funds, Public Debt immediately invests all receipts credited to the Fund, and maintains the invested assets in the Trust Fund account until money is needed by the related Federal Program agency to fund program activity, such as Social Security and unemployment benefit payments, as well as highway funding.

When the program agencies determine that monies are needed, Public Debt redeems securities from the Funds' investment balances, and transfers the cash proceeds, including interest earned on the investments, to the program accounts for disbursement by the agency. The Bureau provides monthly and other periodic reporting to each Fund's program agency.

Data for Federal Debt Charts - Fiscal Year 2013 and 2018

Source: The Cultural Economist