This article appeared in the February 2014 issue of Globe Asia.

Most who have graded Prof. Ben Bernanke’s twelve years at the Federal Reserve have issued marks which range from A to a gentleman’s C. I think those marks are much too generous. Indeed, I think a failing mark would be more appropriate.

In the ramp up to Britain’s Northern Rock bank run in 2007 and the Lehman Brothers’ bankruptcy in September 2008, Bernanke and the Fed created a classic aggregate demand bubble: when final sales to domestic purchasers — a good proxy for aggregate demand — surge well above the trend rate of growth consistent with modest inflation. The Fed also facilitated the spawning of many market-specific bubbles in the housing, equity, and commodity markets. True to form, Fed officials have steadfastly denied any culpability for creating the bubbles that so spectacularly burst during the Panic of 2008-09.

[Hear More: Former Fed President Admits Central Banking, Paper Money a "Confidence Game"]

The pre-2008 crisis bubble was set off by the Fed’s liquidity injections which were initially designed to fend off a false deflation scare in late 2002. That’s when then-Fed Governor Bernanke sounded a deflation alarm in a dense and noteworthy speech before the National Economists Club. Bernanke convinced his Fed colleagues that a deflation danger was lurking. As then-Chairman Alan Greenspan put it, "We face new challenges in maintaining price stability, specifically to prevent inflation from falling too low".

To fight the alleged deflation threat, the Fed pushed interest rates down sharply. By July 2003, the Fed funds rate was at a then-record low of 1 percent, where it stayed for a year. This artificially low interest rate — compared to the natural or neutral rate at that time, in the 3-4 percent range — induced investors to aggressively speculate by chasing yield in "risky" venues and to ramp up their returns by increasing the amount of leverage they applied. These activities generated asset bubbles and created hot-money flows to developing countries.

However, as the accompanying chart shows, the Fed’s favorite inflation target—the consumer price index, absent food and energy prices—increased by only 12.4 percent over the entire 2003–08 (Q3) period. The Fed’s inflation metric signaled "no problems".

But, as the late Prof. Gottfried Haberler emphasized in 1928, "the relative position and change of different groups of prices are not revealed, but are hidden and submerged in a general [price] index". Unbeknownst to the Fed, abrupt shifts in major relative prices were underfoot. For any economist worth his salt, these relative price changes should have set off alarm bells. Indeed, sharp changes in relative prices are a signal that, under the deceptively smooth surface of a general price index of stable prices, basic maladjustments are probably occurring. And it is these maladjustments that, according to Haberler, hold the key to Austrian business cycle theory — and, I would add, a key to understanding the current crisis.

Just which sectors realized big swings in relative prices during the last U.S. aggregate demand bubble? Housing prices, measured by the Case-Shiller home price index, were surging, increasing by 45 percent from the first quarter in 2003 until their peak in the first quarter of 2006. Share prices were also on a tear, increasing by 66 percent from the first quarter of 2003 until they peaked in the last quarter of 2007. The most dramatic price increases were in commodities, however. Measured by the Commodity Research Bureau’s spot index, commodity prices increased by 92 percent from the first quarter of 2003 to their pre-Lehman Brothers peak in the second quarter of 2008.

In addition to the bubbles spawned in the U.S., the Fed’s artificially low interest rates set off a wild yield-chasing scramble and leveraging lunacy. This gave rise to bubbles abroad and currency war polemics. The accompanying carry trade chart shows the massive increase in U.S. assets abroad. These were fueled by hot-money flows during the Bernanke years.

[You May Also Like: On Its 100th Birthday, the Fed Gives the World Another Stock Market Bubble]

Artificial credit-created investment booms sow the seeds of their own destruction. With the Fed funds rate well below the natural rate in 2003, a credit boom was off and running. And as night follows day, a bust was just around the corner. As usual, it was punctuated by bankruptcies and a landscape littered with malinvestments made during the boom.

While operating under a regime of inflation targeting and a floating U.S. dollar exchange rate, Chairman Bernanke also saw fit to ignore fluctuations in the value of the dollar. Indeed, changes in the dollar’s exchange value did not appear as one of the six metrics on "Bernanke’s Dashboard"—the one the chairman used to gauge the appropriateness of monetary policy. Perhaps this explains why Bernanke has been so dismissive of valid questions suggesting that changes in the dollar’s exchange value influence either commodity prices or more broad-based gauges of inflation.

As Nobelist Prof. Robert Mundell — one of the founding fathers of modern supply-side economics — has convincingly argued, changes in exchange rates transmit inflation (or deflation) into economies, and they can do so rapidly. This was the case during the financial crisis.

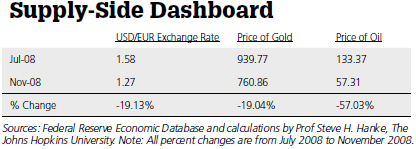

By ignoring this, Bernanke was flying blind in the initial months of the crisis. In consequence, the Fed failed to stabilize the USD/EUR exchange rate, which swung dramatically in the months surrounding the collapse of Lehman Brothers in September 2008 (see the accompanying table). This in turn created wild swings in the prices of gold and oil. In addition, the annual inflation rate measured by the Consumer Price Index plunged from 5.6% in July 2008 to -2.1% in July 2009. With the demand for greenbacks and safe assets (read: U.S. Treasuries) soaring, the Fed was way too tight and didn’t even know it.

In addition to not displaying the dollar’s exchange rate, Chairman Bernanke’s Dashboard didn’t concern itself with money-supply gauges. For Bernanke, it was all about an inflation target. As long as the Fed hit a designated level of inflation, the Fed could wash its hands of all other responsibilities. As Prof. Lars Svensson, deputy governor of Sweden’s Riksbank — the world’s first central bank — and a well-known pioneer of inflation targeting put it: "My view is that the crisis was largely caused by factors that had very little to do with monetary policy". What nonsense.

[Related: Steve Forbes: The Federal Reserve Leadership Has No Idea What They're Doing]

For central bankers, including Bernanke, the name of the game is to blame someone else for the world’s economic and financial troubles. Indeed, as part of the Fed’s blame game, its accusatory finger has been pointed at commercial bankers. The central banking establishment asserts that banks are too risky and dangerous because they are "undercapitalized" and "underregulated". It is therefore not surprising that the Bank for International Settlements in Basel, Switzerland (the central bankers’ bank) has issued new Basel III capital rules that will bump up banks’ capital requirements. And if that isn’t bad enough, the Fed has embraced many new regulations contained in the Dodd-Frank legislation. All this regulatory zeal has created a credit crunch. This has resulted in a damaging pro-cyclical policy stance in the middle of a slump — just what we don’t need.

But, how could this be? After all, central banks around the world have turned on the money pumps. Shouldn’t this be ratcheting up money supply growth?

The problem is that central banks only produce what Lord John Maynard Keynes referred to in 1930 as "state money". And state money (also known as base or high-powered money) is a rather small portion of the total "money" in an economy. The commercial banking system produces most of the money in the economy by creating bank deposits, or what Keynes called "bank money".

Since August 2008, the month before Lehman Brothers collapsed, the supply of state money has more than quadrupled, while bank money has shrunk by 12.1 percent — resulting in an anemic increase of only 4.5 percent in the total money supply (M4) (see the accompanying chart). The public is confused — as it should be. After all, the Fed has embraced contradictory monetary policies. On the one hand, when it comes to state money, the Fed has been ultra-loose. But, on the other hand, when it comes to the largest component of the money supply, bank money, a tight monetary stance has been embraced.

Prof. Bernanke’s days at the Fed have been marked by monetary misjudgments and malfeasance. Since the proof of the pudding should be in the eating, zero stars in the Michelin Guide.

Steve H. Hanke is Professor of Applied Economics at the Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, MD. He is also a Senior Fellow and Director of the Troubled Currencies Project at the Cato Institute in Washington, D.C. You can follow him on Twitter: @Steve_Hanke