What’s the difference between a correction and a bear market? This seems like a straightforward question, but if your answer has anything to do with percentage declines (as in, a correction is a drop greater than 10%, while a bear market is a decline greater than 20%), you’re missing the point.

While those are the generally accepted thresholds that the financial media uses to define corrections and bear markets, I’d argue those definitions are completely arbitrary and serve little purpose other than general classification.

The real difference between a correction and a bear market lies in the reason for the decline, not in the magnitude.

A correction is called a correction because the price has overshot trend, and thus has to “correct” itself. Corrections occur when both the primary trend in the stock market is bullish, and the economy is expanding. They represent a period of consolidation after prices have risen too far, too fast.

Check out Bond Market Experiencing Biggest Technical Change in Our Lifetimes, Says Strategist

A bear market, on the other hand, is a situation in which the primary trend itself has rolled over. This is nearly always a reflection of deteriorating economic conditions, which is why bear markets and economic recessions go hand in hand.

In a bear market, prices are not falling because they’ve overshot trend, they’re falling because the economy itself is deteriorating and the outlook for corporate profits is falling. In other words, corrections represent a counter-trend move, while bear markets are trend-following in nature, tracking the direction of the economy as it heads south.

What makes deciphering corrections from bear markets so difficult is the notion that stock markets discount future economic conditions. When prices initially fall, we’re left wondering, “Is the primary trend still bullish? Or is the stock market discounting an approaching recession?”

I think that I and others here at Dow Theory Letters have effectively answered that question to the best of our ability, so I don’t want to spend time on that today. What I do want to focus on is the notion that corrections are a healthy and necessary part of any bull market.

You might not feel healthier after last week’s gut-wrenching moves, but I can assure you that the market in general, along with the psyches of global investors, is now in a better place because of it.

Big drops like we had last week instill in us a sense of fear, and that helps us to become more prudent risk takers. Perhaps you, like others, did not realize how much risk you were taking until last week. If that’s the case, then you should appreciate your newfound perspective. Sometimes it requires having a “close call” to wake us up from our complacency.

Read also Expect Further Market Melt-Up After Pullback, Says Jeff deGraaf

Corrections also tamp down expectations, and this can help to prolong the duration of a bull market. Recall that investing is always a game of expectations and that stocks only rise when the outlook improves. Having a reset of expectations allows market participants an opportunity to regroup, to make sure that the madness of crowds has not completely overtaken the financial markets.

Finally, corrections are useful because they take us back toward the longer-term trend. I don’t know about you, but I like the idea of slow, sustainable growth more than I enjoy riding financial roller coasters. Corrections help to ensure that we don’t overshoot the longer-term trend by too far, which, at least in theory, implies that returns should be more consistent and predictable. That’s something everyone can appreciate.

Moving on, I’d like to talk briefly about what initially triggered this correction: fears of rising inflation and higher interest rates. My take is that these fears are a bit overblown, but, of course, I could be wrong.

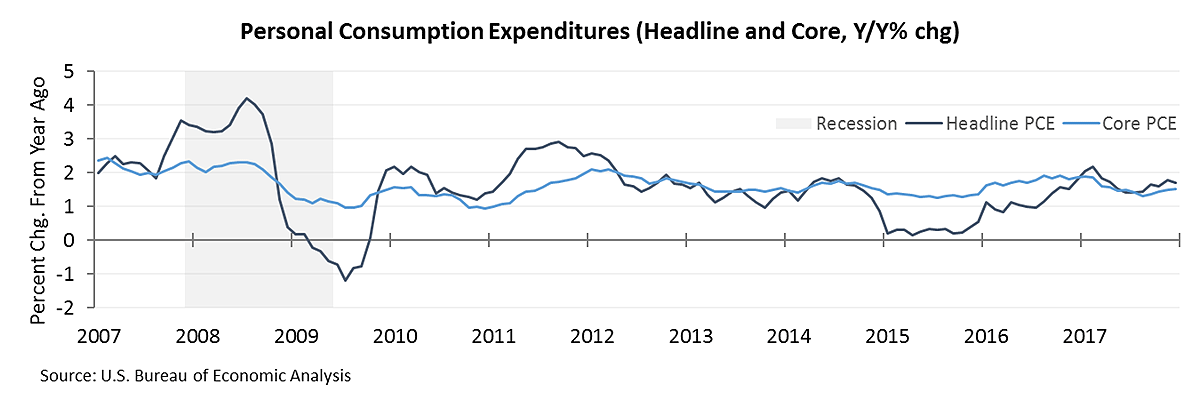

To begin, it’s important to point out that this selloff was not triggered by rising inflation, but by fears of rising inflation. The chart below shows the Fed’s preferred measure of inflation, the PCE, and as you can see, core inflation remains stuck well below their 2% target.

In fact, core PCE has only risen 1.5% over the past year. Not only that, it’s been six years since the Fed last achieved their 2% core inflation target, and that was very fleeting.

Now take a look at market-based measures of inflation expectations. Using the spread between Treasuries and TIPS, we can see that inflation expectations recently spiked. Investors now believe that inflation will average 2.3% over the next five years.

Without a doubt, it was this spike in inflation expectations that drove interest rates higher, which triggered the selloff. This was compounded by data showing wages rising 2.9% through January, the fastest pace since 2009. The real question now is whether actual inflation will rise to match expectations, or if expectations will subside as they have in the past.

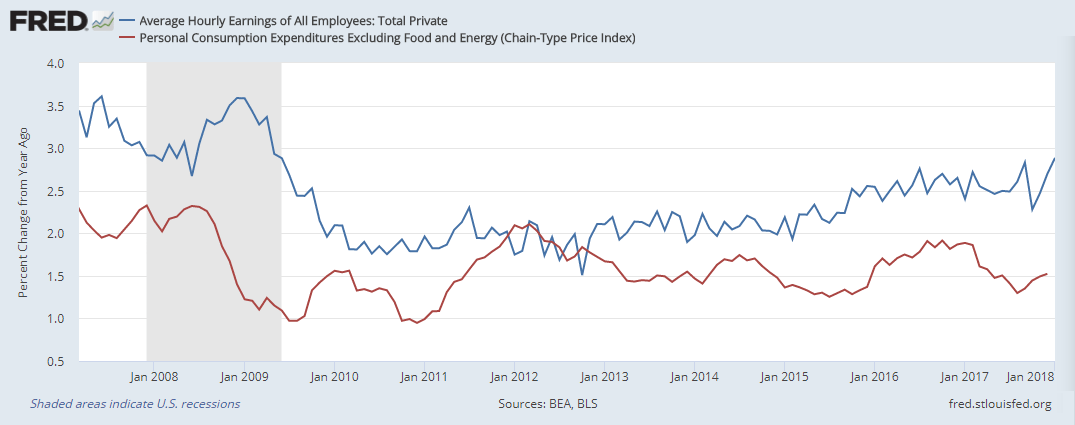

One clue has to do with the breakdown in wage gains. As the chart below shows, aggregate wage growth may have hit a post-recession high, but it’s being unevenly distributed. A closer look shows that wage gains for nonsupervisory workers (about 80% of the workforce) are lagging behind that of their managerial counterparts. Wage growth for this group is stuck at about the same level we’ve seen for the past two years (green line below).

Also, it’s worth pointing out that the link between wage gains and core inflation is modest at best. Last week, Fed President James Bullard went so far as to say that the relationship between inflation and labor market conditions “has broken down in recent years and may be zero.”

I think that’s somewhat of an overstatement, but he’s not incorrect in observing that core inflation and wage gains share little correlation. As you can see in the chart below, wage gains (blue line) have averaged a steady 2-2.5% during the recovery, while core inflation (red line) has acted as an oscillator moving between 1 and 2%.

This implies that there is much more to the inflation story than wage growth, and perhaps the markets got a little too freaked out by last month’s jobs report.

By the way, if you’re wondering why I keep referring to “core” inflation, which excludes food and energy, instead of headline inflation, the reason is because that’s the Fed’s preferred measure for setting monetary policy. Food and energy prices are subject to myriad other forces which make them extremely volatile. Excluding these items provides a better picture of how inflation is impacting the underlying economy.

And speaking of the Fed, investors (and the Fed as well) would do well to remember that monetary policy always acts with a lag. That means we may not be feeling the full impact of prior rate hikes yet, as they take a while to trickle through the system. Moving forward, these past rate hikes could continue to exert downward pressure on growth and inflation.

But regardless of what happens with inflation, we do have a new bogey on our screens to watch, and that’s the 10-year Treasury yield. This bellwether yield represents a proxy for the demand for bonds vs. stocks, and it’s now at a level where further increases will start to exert downward pressure on stocks.

This is not to say that the run in stocks is over, only that for the first time in a while, bond yields are now becoming competitive and warrant our attention as a potential threat moving forward.

The preceding content was an excerpt from Dow Theory Letters. To receive their daily updates and research, click here to subscribe. Matt is also the Chief Investment Strategist at Model Investing. For more information about algorithmic based portfolio management, click here.