The contrast in approach to central banking between the U.S. Federal Reserve (Fed) and the European Central Bank (ECB) is remarkable. ECB President Draghi has done more to lift market concerns with a targeted strategy than Bernanke’s blunt attempts. In announcing the Outright Monetary Transactions (OMT) program, Draghi not only shored up market concerns, but also forced upon European policy makers a pathway for a fiscal framework and centralized fiscal oversight. From a currency perspective, such steps may serve to bolster the euro. In contrast, Bernanke appears willing to do all the heavy lifting on the economy while gridlock remains in Washington. We fear that the unintended consequences of such accommodative policies may undermine the U.S. dollar over the foreseeable future, and ultimately pose significant risks to the U.S. economy.

The conditionality of the ECB’s OMT program announced in September is an important step, as it effectively takes away sovereignty over a participating country’s fiscal decision-making process. The program, in which the ECB may engage in unlimited, but sterilized, purchases of short-term government bonds of Eurozone countries, is conditional on governments applying for help and ceding sovereign control over their budgets. It also forces Euro-area politicians to agree upon fiscal limits and targets, as well as the oversight and implementation of such measures. Importantly, it is not up to the ECB to determine whether the governments receiving help are abiding by the rules imposed on them, maintaining the ECB’s independence. We believe the OMT program encourages the Eurozone to move closer to a currency union with a defined process on how to address fiscal challenges.

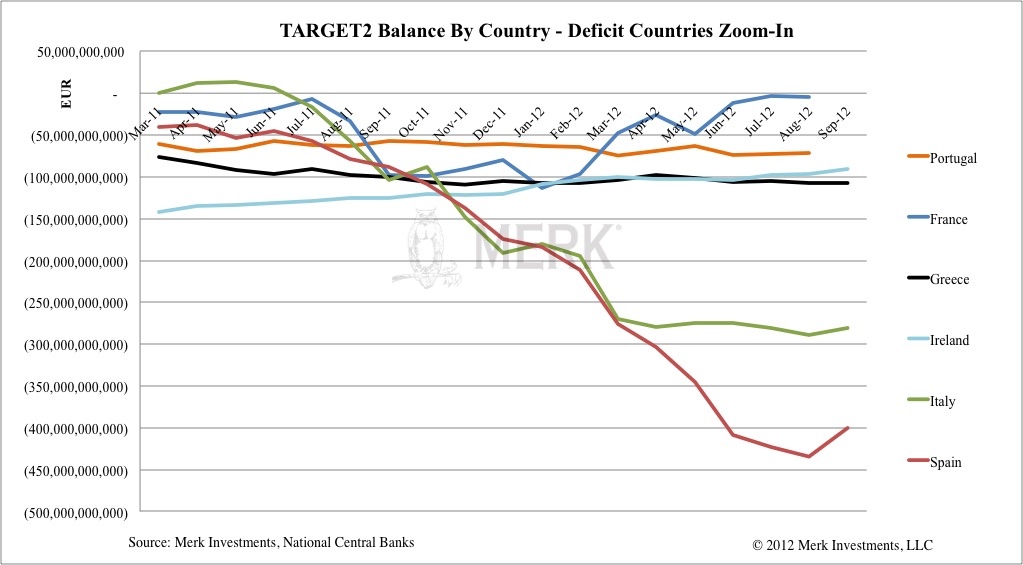

Ultimately, for the ECB to act effectively as an independent central bank, and for the euro to act as any other free-floating currency, European politicians need to act as a fiscal union. The establishment of centralized fiscal oversight is thus a necessary precondition for the long-term sustainability of the monetary union. At the same time, by explicitly stating its intention to stand behind European countries as a backstop and do “whatever it takes” to ensure the viability of the euro, the ECB has taken some of the tail risk, or “black swan” risk, out of markets. Improvements in Target 2 balances within the region are clear in the following chart:

Despite recent improvements, we foresee ongoing market volatility. We have argued for a very long time that Europe’s problems will not be fixed overnight, but rather, are likely to be a long-drawn out, somewhat dysfunctional, process. Politicians are not incentivized to act until the bond market forces them to act. We currently see this dynamic playing out in Spain: as soon as market pressure abates – i.e., interest rates fall to more manageable levels – politicians become reticent to ask for help; after all, in asking for help they must give up control over the country’s fiscal decisions. Unfortunately, for this very reason, we believe volatility is a necessary prerequisite for progress to be made in Europe; it is only when interest rates are at unsustainable levels that politicians are forced to act. That said, it may be a long, messy process but giant steps have now been put in place towards centralized fiscal oversight of the Eurozone. From a currency perspective, we view these steps positively for the euro.

Another important development in Europe are the talks surrounding centralized oversight of the banking industry. We believe the ECB is correct to push for implementation of a single supervisory mechanism for Euro-area banks. Such a mechanism is important in lessening the disparity among Euro-area nation financial industries and may help to reduce future crises. It is simply unsustainable for each member country to oversee its respective banking industry as it inherently increases geographical contagion risks, exacerbating downside economic pressures.

The existence of a centralized banking oversight mechanism may help lessen the probability of runs on the banking industry of select countries. For instance, banks domiciled in weak periphery nations have been the target of short selling and depositor withdrawals, largely because those same banks have significant exposure to the downgraded sovereign debt of the countries in which they are domiciled. Greek banks held a significant proportion of Greek government debt on their balance sheets. Likewise, Spanish banks have significant exposure to Spanish government debt. The same is true for Italian or Portuguese banks. Aside from lack of consistency and uniformity, a key problem with individual country banking regulation is that each respective regulator deems local sovereign debt “risk free”, thereby incentivizing the local banking industry to be overexposed to that same sovereign debt. Having a centralized banking oversight mechanism may help alleviate these concerns. The process towards centralized oversight is unlikely to be a quick or smooth one, as there are so many vested interests, but positive steps appear to be being made.

It is important to note that despite all the concerns surrounding Europe, the euro is not trading at parity to the U.S. dollar. In fact, the euro has held its value relatively well. We believe one of the reasons for this is the fact that the Eurozone as a whole has a broadly balanced current account. In contrast, the U.S. has a massive current account deficit, meaning the U.S. is reliant on investment from abroad simply to stop the dollar from falling. As a result, the U.S. is required to generate economic growth to attract capital from abroad. The euro doesn’t have this same pressure.

In addition, the ECB has been more refrained in implementing accommodative policies relative to the Fed. The ECB has the single mandate of ensuring price stability as opposed to the Fed’s dual mandate of fostering price stability and maximum employment, the latter of which is its justification for extensive and ongoing monetary easing. Like any asset, when there is an increase in supply with no offsetting increase in demand, this naturally creates downward pressures on price. We believe such dynamics are playing out in the U.S., especially on the back of QE3, and are less evident in Europe. While concerns remain over the future direction of Europe, we consider that U.S. monetary policies are more detrimental to the value of the U.S. dollar. As a result, we believe the euro may appreciate relative to the U.S. dollar going forward.

In our opinion, the ECB has done a good job in maintaining its independence, while not encroaching on fiscal policy, but rather forcing upon policy makers a process by which they can make steps towards fiscal co-ordination. In contrast, the U.S. Fed has once again encroached on fiscal territory in setting monetary policy. By announcing QE3 and its open-ended, unlimited purchases of mortgage-backed securities (MBS), the Fed is specifically favoring one portion of the economy over others: the housing sector. It’s not hard to see why. We believe Bernanke wants to instigate home price inflation and, in so doing, bail out the millions still underwater in their mortgages. Gridlock in Washington has meant Bernanke has taken it upon himself to address the issue. The problem is, funneling funds to certain sectors of the economy has traditionally been the realm of fiscal policy, NOT monetary policy. We saw what happened in the aftermath of the first round of MBS purchases: Bernanke was hauled in front of Congress and the House on numerous occasions to explain his actions. Such political pressure only serves to undermine the independence of the Fed; empirical evidence supports the notion that the more independent a central bank is, the greater the likelihood of price stable environments.

QE3 appears to have been effective in raising inflationary concerns. Indeed, market implied measures of inflation increased significantly in reaction to the announcement. Our concern is Bernanke and the Fed will now err on the side of inflation in attempting to drive the unemployment rate lower. The September Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) minutes make it clear that the Fed would like to introduce a numerical target for the unemployment rate, looking to move away from a focus on moderating inflation and placing a greater emphasis on trying to improve the employment situation. This change in focus is worrying, as it further severs the link between monetary policy and inflation.

Source: Merk Funds