While Treasuries are said to have no default risk as the Federal Reserve (Fed) can always print money to pay off the debt, hidden risks might be lurking. As oxymoronic as it may sound, the biggest risk to the economy and the U.S. dollar might be, well, economic growth! Let us explain.

The U.S. government paid an average interest rate of 2.046% on the .0 trillion of Treasuries outstanding as of the end of November. Treasuries include Bills, Notes, Bonds and Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities (TIPS). At 2.046%, the cost of carrying the Treasury portfolio currently costs the government 5 billion per annum; about 6% of the federal budget was spent on servicing the national debt. 1

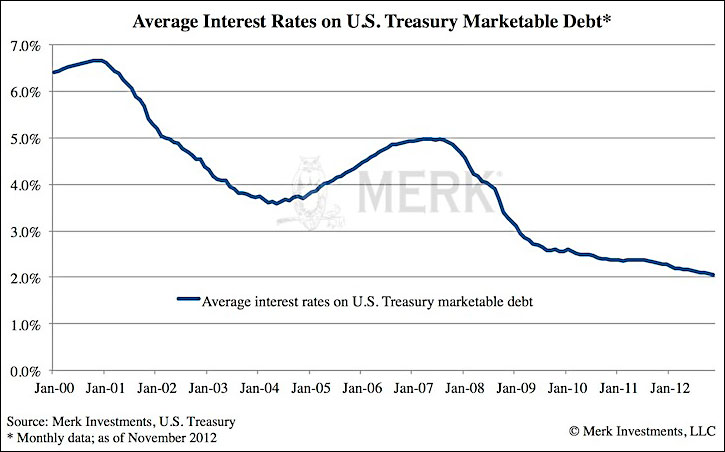

While total government debt has ballooned in recent years, the interest rate paid by the government on its debt has continued on its downward trend:

We only need to go back to the average interest rate paid in 2001, 6.19%, and the annual cost of servicing Treasuries would triple, paying more than Greece as a percentage of the budget. Not only would other government programs be crowded out, the debt service payments might likely be considered unsustainable. Except for the fact that, unlike Greece, the Fed can print its own money, diluting the value of the debt. In doing so, the debt could be nominally paid, although we would expect inflation to be substantially higher in such a scenario.

These numbers are no secret. Yet, absent of a gradual, yet orderly decline of the U.S. dollar over the years – with the occasional rally to make some investors believe the long-term decline of the U.S. dollar may be over - the markets do not appear overly concerned. Reasons the market aren’t particularly concerned include:

- The average interest rate continues to trend downward. That’s because maturing high-coupon Treasury securities are refinanced with new, lower yielding securities.

- Treasury Secretary Geithner has diligently lengthened the average duration of U.S. debt from about 4 years when he took office to currently over 5 years.

For the U.S. government, a longer duration suggests less vulnerability to a rise in interest rates, as it will take longer for a rise in borrowing costs to filter through to the average debt outstanding. The opposite is true for investors: the longer the average duration of a bond or a bond portfolio one holds, the greater the interest risk, i.e. the risk that the bonds fall in value as interest rates rise.

Operation Twist to hide interest risk

Debt management by the Treasury only tells part of the story on interest risk. When the Treasury publishes “debt held by the public,” it includes Treasuries purchased in the open market by the Fed. By engaging in “Operation Twist”, the Federal Reserve stepped onto Timothy Geithner’s turf, manipulating the average duration of debt held by the private sector. Notably, the private sector holds fewer longer-dated bonds, as the Fed has gobbled many of them up.

However, investors may still be exposed to substantial interest risk in their overall fixed income holdings as, in the search of yield, many have doubled down by seeking out longer dated and riskier securities.

The Fed, many are not aware of, employs amortized cost accounting, rather than marking its holdings to market, thus hiding potential losses should interest rates go up and its portfolio of Treasuries and Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS) fall in value.

Quantitative easing to increase interest risk

Whenever there’s a warning that all the money created by the Federal Reserve is akin to printing money, some dismiss these concerns as the money created out of thin air to buy securities has not caused banks to lend, but park excess reserves back at the Federal Reserve. As of December 14, 2012, .4 trillion in excess reserves is parked at the Fed. Substantial interest risk might be baked into reserves:

Consider that the Fed has been paying about billion in profits to the Treasury in recent years. Think of it this way: the more money the Fed “prints”, the more (Treasury & MBS) securities it buys, the more interest it earns. That’s why Fed Chair Bernanke brags that his policies have not cost taxpayers a cent, even if the activities may put the purchasing power of the currency at risk. Now, Bernanke has also claimed he could raise rates in 15 minutes. In our assessment, it’s most unlikely he would do so by selling long-dated securities; instead, in an effort to keep long-term rates low, the most likely scenario is that the Fed will pay a higher interest rate on reserves. Up until the financial crisis broke out, the Federal Reserve would have intervened in the Treasury market by buying and selling securities to move short-term interest rates. In the fall of 2008, the Fed was granted the authority by Congress to pay interest on reserves.

As interest rates rise, not only will Treasury pay more for debt it issues, it may also receive less from the Fed. Interest rates would have to rise to about 6% for the entire billion in “profits” to be wiped out assuming a constant .5 trillion in reserve balances (.4 trillion in excess reserves and __spamspan_img_placeholder__.1 trillion in required reserves that also receive interest); that assumes, the Fed does not grow its balance sheet in the interim (in an effort to generate more “profits” for the Fed) and would not reduce its payouts in the interim as a precaution because bonds held on the Fed’s books may be trading in the market at substantially lower levels.

Should interest rates move up, the Treasury may no longer be able to rely on the Fed to finance the deficit (while the Fed denies the purposes of its policies is to finance the deficit, the Fed is buying a trillion dollars in debt as the government is running a trillion dollar deficit).

Biggest risk: economic growth?

In our surveys, inflation tends to be on top of investors’ minds, no matter how often government surveys show us that inflation is not the problem. Should inflation expectations continue to rise – and a reasonable person may be excused for coming to that conclusion given that the Fed appears to be increasingly focusing on employment rather than inflation – bonds might be selling off, putting upward pressure on the cost of borrowing for the government.

But if we assume inflation is indeed not an imminent concern (keep in mind that the Fed is also buying TIPS and, thus, distorting important inflation gauges in the market), we only need to look back at the spring of this year when a couple of good economic indicators got some investors to conclude that a recovery is finally under way. What happened? The bond market sold off rather sharply! A key reason why the Fed is increasingly moving towards employment targeting is to prevent a recurrence, namely a market-driven tightening, pushing up mortgage costs.

The government should be grateful that we have this “muddle-through” economy. Let some of that money that’s been printed “stick;” let the economy kick into high gear. In that scenario, the “good news” may well be reflected in a bond market that turns into a bear market.

Historically, when interest rates move higher in an economic recovery, the U.S. dollar is no beneficiary because foreigners tend to hold lots of Treasuries: should the bond market turn into a bear market, foreigners historically tend to wait for the end of the tightening cycle before recommitting to U.S. Treasuries.

The point we are making is that for bonds to sell off and the dollar to be under pressure, we don’t need inflation to show its ugly head; we don’t need China or Japan to engage in financial warfare by dumping their Treasury holdings. All we may need is economic growth! And while Timothy Geithner has studiously been trying to extend the average duration of U.S. debt, Ben Bernanke at the Fed has thrown him a curveball.

Perception is reality

One only needs to look at Spain to see that a long average duration of government debt is no guarantor against a debt crisis. Spain has an average maturity of government debt of 6 years, yet it does not take a rocket scientist to figure out that borrowing at 6% in the market is not sustainable given the total debt burden. As such, markets tend to shiver when confidence is lost, even if, technically, governments could cling on for a while when the cost of borrowing surges.

History may repeat itself

It was only 11 years ago that the US government paid and average of 6% on its debt. Sure the average cost of borrowing has been coming down. But no matter what scenarios we paint, if the average cost of borrowing can come down to almost 2% from 6%, we believe it is entirely possible to have the reverse take place over the next 11 years. Given the additional risks the Fed’s actions have introduced, the timing could well be condensed. But even if not, we believe it is irresponsible for policy makers to pretend interest rates may stay low forever (except, maybe, Tim Geithner’s steps to increase the average maturity of government debt; but as pointed out, his efforts may be overwhelmed by those of the Fed).

Fiscal Cliff

What’s so sad about the discussion about the so-called fiscal cliff is that even the initial Republican proposal results in approximately 0 billion deficits each year. Financed at an average 2%, this would add over 0 billion in interest expenses over ten years; financed at an average 4%, it would add almost trillion in interest expense over ten years. Mind you, this is a politically unrealistic, conservative proposal. Democrats pretend we don’t even have a long-term sustainability problem, only that the wealthy don’t pay their fair share.

In our humble opinion, both Republicans and Democrats are distracted. In many ways, the simultaneous increase in taxes and cut in expenditures of the fiscal cliff is akin to European style austerity: if the cliff were to take place in its entirety, we would a) suffer a significant economic slow down; b) continue to run deficits exceeding 3% of GDP before factoring in any slowdown; and c) still not have fixed entitlements.

Entitlements

While our discussion focused on trillion in Treasury securities, the so-called “unfunded liabilities” go much further than the trillion in accounting liabilities set aside. Depending on the actuarial assumptions, unfunded liabilities may be as high as trillion to 0 trillion or higher.

In our assessment, the only way to tame the explosion of government liabilities over the medium term is to tame entitlements. But it is very difficult to cut back on promises made. As Europe has shown us, the only language that policy makers understand may be that of the bond market. As such, unless and until the bond market imposes entitlement reform, we are rather pessimistic that our budget will be put on a sustainable footing. Put another way, things are not bad enough for policy makers to make the tough decisions.

Different from Europe, however, the U.S. has a current account deficit. As a result, a misbehaving bond market may have far greater negative ramifications for the dollar than the strains in the Eurozone bond markets had for the Euro. In the Eurozone, the current account is roughly in balance; while there was a flight out of weaker Eurozone countries, that flight was mostly intra-Eurozone towards Germany and Northern European countries.

So while the default risk of U.S. Treasuries may be less than that of Eurozone members, the risks to the purchasing power of the U.S. dollar might be substantially higher. On that note, while the Fed has indicated to buy another approximately trillion in assets over the next year, we would not be surprised to see the balance sheet of the more demand-driven European Central Bank shrink as some banks pay back loans from the Long-Term Refinancing Operation (LTRO) early.

In early January, we will be publishing our outlook for 2013; Please also sign up for our newsletter to be informed as we discuss global dynamics and their impact on gold and currencies. Additionally, please join us for our upcoming Webinar on Tuesday, January 15th, 2013.

Source: Merk Funds