Efforts are underway to undermine Switzerland’s rock solid reputation as a safe haven. The alpine nation, famous for its readiness against enemies with citizens storing military assault rifles at their homes, is under attack. The attack, however, comes from one of their own, the guardian of the Swiss franc: the Swiss National Bank (SNB). In any other country, a central bank may have the power to derail the currency; in Switzerland, however, efforts to undermine the franc may be more appropriately characterized by a Don Quixotian battle by a lone warrior, a warrior armed with a license to print money.

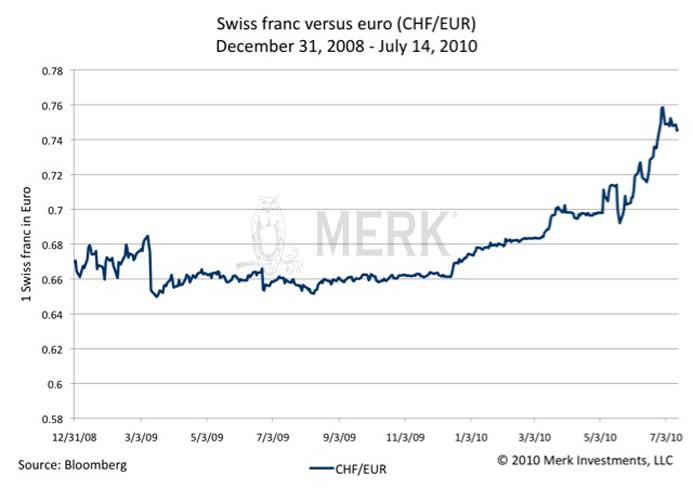

Prices, be they for goods and services, stock prices or currencies, are best set by free markets. The euro and the Swiss franc are traditionally two highly correlated currencies; however, there are rational reasons why each currency has periods of strengths and weakness. SNB Chairman Philipp Hildebrand does not appear to see it that way; he was on a mission against “speculators” that gauged the Swiss franc to be a safer place than the euro. As his influence rose in early 2009 (his promotion from Vice President to Chairman was announced in early 2009, but did not take effect until early 2010), Switzerland began to intervene in the currency markets, apparently with the aim of pegging the Swiss franc to the euro. Below is a chart of the Swiss franc versus the euro over this time period (a rising trend reflects Swiss franc strength versus the euro); sharp moves downward tend to coincide with larger interventions to “punish” speculators:

As the Greek crisis intensified, it became ever more difficult for the SNB to achieve its goals. It appears to us that investors scared of any fallout from Greece were treated as enemy combatants for seeking refuge in the Swiss franc. It is mindboggling to brandish those diversifying from the euro to the Swiss franc as speculators. Without a doubt, the Greek tragedy made the euro appear riskier to rational investors. There’s a perception at the SNB that a strong Swiss franc versus the euro hurts Swiss exports – the SNB prefers to use the more dramatic and over-used term deflation. On the margin, that may well be true, but consider:

- Switzerland’s strength has never been to compete on cost. Keeping a currency weak for competitive reasons is something stronger Asian countries may be in the process of relaxing because these policies may have caused inflationary pressures to build.

- Swiss firms have extensive experience in dealing with fluctuating exchange rates, as well as a strong Swiss franc.

- Swiss multi-nationals generally have foreign subsidiaries through which currency exposures of revenues and expenses can be more easily aligned.

- Swiss watchmakers are complaining because of the high price of gold, not the strong Swiss franc. Indeed, a stronger Swiss franc would alleviate some of these additional cost pressures.

- Most importantly, Swiss banks depend on the trust in the Swiss franc. It’s bad enough that Swiss bank secrecy has more holes than Swiss cheese. If the SNB were to succeed in actually weakening the Swiss franc in a meaningful way, the confidence loss in the banking industry may easily exceed the short-term benefit of boosting exports.

In early 2009, before the first interventions took place, we wondered how effective such a strategy could be. When Japanese policy makers make threats to intervene to weaken the yen, we take them very seriously; after all, the Japanese might be willing and able to destroy their currency in a possibly fruitless effort to boost their economy (see our January 2009 analysis Yen’s Kamikaze Flight Trajectory). But the Swiss? Would the SNB go all the way in their effort to weaken their currency? Our judgment has been that it is unlikely; history so far seems to prove us right. However, because of the disconnect between the talk and action, the Swiss National Bank’s policy is not fighting, but encouraging speculation. Each time the SNB intervenes to weaken the Swiss franc, it may be a gift to speculators, as they can buy the Swiss franc at a discount.

It’s not just cultural reasons why the SNB is unlikely to succeed on a “kamikaze mission”: Switzerland’s public finances are too sound to be easily wrecked by a rogue national bank. While Switzerland’s debt-to-GDP ratio is reasonably low by international standards, the country’s discipline slipped during the 1990s; during the period, the gross debt-to-GDP ratio (including federal, cantonal and communal debt) rose from 31 to 54 percent; during the same period, Ireland, Portugal, Belgium, Netherlands and Denmark all reduced their debt-to-GDP ratios (source: 2002 IMF Working Paper on Swiss Debt Brake). As Swiss debt-to-GDP ratios climbed, a movement in Switzerland was born that eventually led to a constitutional amendment that requires a balanced budget over a business cycle: the balanced budget amendment, commonly referred to as the Swiss Debt Brake, was passed in 2001 and implemented in 2003. Without going into the details of how the mechanism works, relevant for our discussion is that the will of the voters imposed fiscal discipline.

There is a very real consequence of a country living within its means: the debt market of that country is not very large. The Swiss debt market is a rather quiet one: investors often buy debt at auctions, then hold them to maturity; since the onset of the financial crisis, Swiss T-Bills have often been auctioned off at face value, meaning buyers get 0% interest for lending their money (or negative interest after commission). In such an environment, quantitative easing or credit easing is more easily said than done: the SNB cannot print money to buy Swiss debt on a grand scale as there are simply not enough sellers around. However, never underestimate the creativity of central bankers: if it is not realistic to buy Swiss franc denominated debt, why not use the Swiss central bank’s balance sheet, i.e. print money, to buy euro denominated debt? An intervention strategy was initiated that allowed Swiss-style quantitative easing, currency intervention, all in the name of fighting deflation and speculation.

Except, that the SNB gamble has not worked. As a result of buying euro, well, the Swiss National Bank’s balance sheet, now holds euro – lots of it; indeed, the SNB now holds significantly more euro than Swiss francs. The SNB may be running out of ammunition as it has a dwindling supply of Swiss francs; theoretically, that should not stop a central bank: indeed, the SNB can create Swiss francs out of thin air (a mere keyboard entry into its accounts) to buy euros. However, politically, it will be an uphill battle for the SNB to claim it is pursuing its Swiss mandate should they almost exclusively hold euros.

Unlike other central banks, the SNB is a publicly traded corporation with shareholders; the Swiss federal government is not a shareholder, but the cantons are; theoretically, anyone can buy shares, subject to availability. While the SNB’s corporate charter has certain special features, most importantly the power to print money, heavy foreign currency exposure may create wide swings in earnings; notably, the SNB may report losses in the billions as a result of its currency interventions (that may turn into substantial profits if and when the euro recovers). While even a negative net worth is mostly a technicality for a central bank, most damaging about such losses is the wrath of the public that may scrutinize the bank in more detail. Swiss citizens have shown that they can impose discipline on fiscal policy; they may very well rein in a SNB not fulfilling the will of the people.

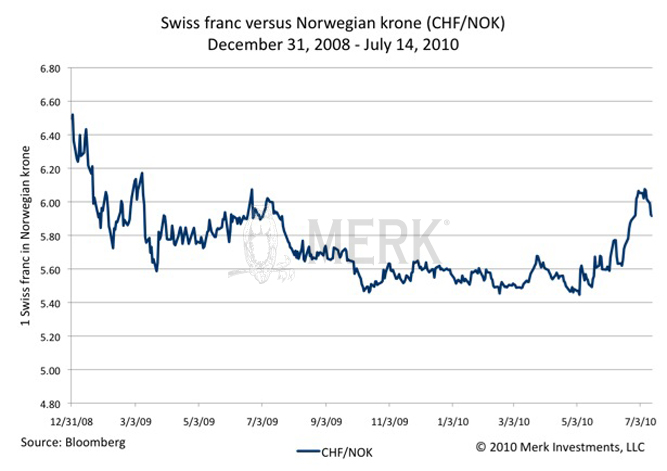

So what is an investor, rather than speculator, to do? In a March 2009 op-ed published in the Financial Times, we cautioned Switzerland may cede its safe haven status to Norway. While we gauged at the time that the SNB’s policies would not lead to its desired long-term devaluation of the Swiss franc, we did anticipate a more negative investment climate for Switzerland as a result of the more activist central bank. We are on record for shifting substantial assets from Switzerland to Norway from early 2009. We started to reduce that position as the SNB’s position became increasingly untenable. Below is a chart of the Swiss franc versus the Norwegian krone (a downward trend reflects Swiss franc weakness relative to the Norwegian krone):

In our assessment, the biggest problem with central bank currency intervention is not whether it is effective or not, but that investors start focusing on possible intervention rather than underlying fundamentals. While this may not be the last fight the SNB puts up, it appears the markets have little confidence the SNB can implement its threats. Indeed, the SNB seems to have looked for a graceful exit to its policies by declaring the threat of inflation over, for the time being. Of course, that announcement spurred a speculative rally, giving the green light to buy Swiss francs. That in turn caused the SNB to state that they may intervene yet again; we would rather have the SNB focus on sound monetary policy than on a cat and mouse game with speculators they are bound to lose.

As policy makers are throwing around billions, if not trillions of dollars, in desperate attempts to enforce their objectives, rational capital allocation suffers, planting seeds for new distortions and bubbles.

In the coming days, the stress test on the eurozone banks will be published; don’t miss our analysis by signing up to our newsletter; we will also give an update on our views in our webinar on July 29, 2010 – please register.