Earlier this week, I wrote an article "Ben Graham's Curse on Gold" for John Mauldin's excellent weekly service, Outside the Box. While the article has been fairly widely picked up - and by those stuck in a conventional mind-set, roundly lambasted (as anticipated) - you might enjoy it.

The article expands on something we touched on in The Casey Reporta few months back, namely that an underlying reason so many mainstream brokers and analysts - and by extension, their clients - have missed the gold bandwagon so far has to do with the blank spot in Benjamin Graham's career, most of which occurred when private gold ownership was illegal. Rather than recap the whole story here, please read it if you haven't yet done so.

Call it a mutual-admiration society, but much of today's edition is dedicated to a very interesting article written by John some years ago on the nature of collapse. I first came across it in his excellent best-seller End Game and was so impressed, I asked him if I could share it with you.

At the end of the article, I'll be back with more thoughts on this and that.

Fingers of Instability

By John Mauldin

"To trace something unknown back to something known is alleviating, soothing, gratifying and gives moreover a feeling of power. Danger, disquiet, anxiety attend the unknown - the first instinct is to eliminate these distressing states. First principle: any explanation is better than none... The cause-creating drive is thus conditioned and excited by the feeling of fear..." Friedrich Nietzsche

This weekend I turn 60 and have been a little more introspective than usual. I am often told that the letter I wrote well over three years ago on ubiquity and complexity theory and the future of the economy was the best letter I have ever done. I went back to read it, and it has aged well. I basically outlined how a financial crisis would unfold, and now it has.

On reflection, I think that there are perhaps other, even larger, events in our future than the recent credit crisis and recession; yet, just as in 2006, there is a great deal of complacency. But as we will see, there are fingers of instability building up that have the potential to create large disruptions, both positive and negative, in our future.

"Any explanation is better than none." -Nietzsche

And the simpler the explanation, it seems in the investment game, the better. "The markets went up because oil went down," we are told (except that when oil went up, then there was another reason for the movement of the markets). But we all intuitively know that things are far more complicated than that. However, as Nietzsche noted, dealing with the unknown can be disturbing, so we look for the simple explanation.

"Ah," we tell ourselves, "I know why that happened." With an explanation firmly in hand, we now feel we know something. And the behavioral psychologists note that this state actually releases chemicals in our brain that make us feel good. We become literally addicted to the simple explanation. The fact that what we "know" (the explanation for the unknowable) is irrelevant or even wrong is not important in achieving the chemical release. And thus we look for reasons.

The credit crisis happened because of Greenspan's monetary policy. Or maybe it was a collective mania. Or any number of things. Just as the proverbial butterfly flapping its wings in the Amazon triggers a storm in Europe, maybe an investor in St. Louis triggered the credit crisis. Crazy? Maybe not. Today we will look at what complexity theory tells us about the reasons for earthquakes, tornados, and the movement of markets. Then we look at how the world and that investor in St. Louis are all tied together in a critical state. Of course, what state and how critical are the issues.

Ubiquity, Complexity Theory, and Sand Piles

We are going to start our explorations with excerpts from a very important book by Mark Buchanan, called Ubiquity: Why Catastrophes Happen. I highly recommend it to those of you who, like me, are trying to understand the complexity of the markets. Not directly about investing, although he touches on it, it is about chaos theory, complexity theory, and critical states. It is written in a manner any layman can understand. There are no equations, just easy-to-grasp, well-written stories and analogies.

As kids, we all had the fun of going to the beach and playing in the sand. Remember taking your plastic buckets and making sand piles? Slowly pouring the sand into an ever bigger pile, until one side of the pile started an avalanche?

Imagine, Buchanan says, dropping one grain of sand after another onto a table. A pile soon develops. Eventually, just one grain starts an avalanche. Most of the time it is a small one, but sometimes it builds on itself and it seems like one whole side of the pile slides down to the bottom.

Well, in 1987 three physicists, named Per Bak, Chao Tang, and Kurt Weisenfeld, began to play the sand pile game in their lab at Brookhaven National Laboratory in New York. Now, actually piling up one grain of sand at a time is a slow process, so they wrote a computer program to do it. Not as much fun, but a whole lot faster. Not that they really cared about sand piles. They were more interested in what are called non-equilibrium systems.

They learned some interesting things. What is the typical size of an avalanche? After a huge number of tests with millions of grains of sand, they found that there is no typical number. "Some involved a single grain; others, ten, a hundred or a thousand. Still others were pile-wide cataclysms involving millions that brought nearly the whole mountain down. At any time, literally anything, it seemed, might be just about to occur."

The piles were indeed completely chaotic in their unpredictability. Now, let's read this next paragraph from Buchanan slowly. It is important, as it creates a mental image that helps me understand the organization of the financial markets and the world economy (emphasis mine).

"To find out why [such unpredictability] should show up in their sand pile game, Bak and colleagues next played a trick with their computer. Imagine peering down on the pile from above, and coloring it in according to its steepness. Where it is relatively flat and stable, color it green; where steep and, in avalanche terms, 'ready to go,' color it red. What do you see? They found that at the outset the pile looked mostly green, but that, as the pile grew, the green became infiltrated with ever more red. With more grains, the scattering of red danger spots grew until a dense skeleton of instability ran through the pile.

"Here then was a clue to its peculiar behavior: a grain falling on a red spot can, by domino-like action, cause sliding at other nearby red spots. If the red network was sparse, and all trouble spots were well isolated one from the other, then a single grain could have only limited repercussions. But when the red spots come to riddle the pile, the consequences of the next grain become fiendishly unpredictable. It might trigger only a few tumblings, or it might instead set off a cataclysmic chain reaction involving millions. The sand pile seemed to have configured itself into a hypersensitive and peculiarly unstable condition in which the next falling grain could trigger a response of any size whatsoever."

Something only a math nerd could love? Scientists refer to this as a critical state. The term critical state can mean the point at which water would go to ice or steam, or the moment that critical mass induces a nuclear reaction, etc. It is the point at which something triggers a change in the basic nature or character of the object or group. Thus (and very casually for all you physicists), we refer to something being in a critical state (or use the term critical mass) when there is the opportunity for significant change.

"But to physicists, [the critical state] has always been seen as a kind of theoretical freak and sideshow, a devilishly unstable and unusual condition that arises only under the most exceptional circumstances [in highly controlled experiments]... In the sand pile game, however, a critical state seemed to arise naturally through the mindless sprinkling of grains."

Thus, they asked themselves, could this phenomenon show up elsewhere? In the earth's crust, triggering earthquakes, or as wholesale changes in an ecosystem - or as a stock market crash? "Could the special organization of the critical state explain why the world at large seems so susceptible to unpredictable upheavals?" Could it help us understand not just earthquakes, but why cartoons in a third-rate paper in Denmark could cause worldwide riots?

Buchanan concludes in his opening chapter, "There are many subtleties and twists in the story ... but the basic message, roughly speaking, is simple: The peculiar and exceptionally unstable organization of the critical state does indeed seem to be ubiquitous in our world. Researchers in the past few years have found its mathematical fingerprints in the workings of all the upheavals I've mentioned so far [earthquakes, eco-disasters, market crashes], as well as in the spreading of epidemics, the flaring of traffic jams, the patterns by which instructions trickle down from managers to workers in the office, and in many other things. At the heart of our story, then, lies the discovery that networks of things of all kinds - atoms, molecules, species, people, and even ideas - have a marked tendency to organize themselves along similar lines. On the basis of this insight, scientists are finally beginning to fathom what lies behind tumultuous events of all sorts, and to see patterns at work where they have never seen them before."

Now, let's think about this for a moment. Going back to the sand pile game, you find that as you double the number of grains of sand involved in an avalanche, the likelihood of an avalanche becomes 2.14 times more likely. We find something similar with earthquakes. In terms of energy, the data indicate that earthquakes become four times less likely each time you double the energy they release. Mathematicians refer to this as a "power law," a special mathematical pattern that stands out in contrast to the overall complexity of the earthquake process.

Fingers of Instability

So what happens in our game? "... after the pile evolves into a critical state, many grains rest just on the verge of tumbling, and these grains link up into 'fingers of instability' of all possible lengths. While many are short, others slice through the pile from one end to the other. So the chain reaction triggered by a single grain might lead to an avalanche of any size whatsoever, depending on whether that grain fell on a short, intermediate, or long finger of instability."

Now, we come to a critical point in our discussion of the critical state. Again, read this with the markets in mind (again, emphasis mine):

"In this simplified setting of the sand pile, the power law also points to something else: the surprising conclusion that even the greatest of events have no special or exceptional causes. After all, every avalanche large or small starts out the same way, when a single grain falls and makes the pile just slightly too steep at one point. What makes one avalanche much larger than another has nothing to do with its original cause, and nothing to do with some special situation in the pile just before it starts. Rather, it has to do with the perpetually unstable organization of the critical state, which makes it always possible for the next grain to trigger an avalanche of any size."

Now, let's couple this idea with a few other concepts. First, Nobel laureate Hyman Minsky points out that stability leads to instability. The more comfortable we get with a given condition or trend, the longer it will persist and then, when the trend fails, the more dramatic the correction. The problem with long-term macroeconomic stability is that it tends to produce unstable financial arrangements. If we believe that tomorrow and next year will be the same as last week and last year, we are more willing to add debt or postpone savings in favor of current consumption. Thus, says Minsky, the longer the period of stability, the higher the potential risk for even greater instability when market participants must change their behavior. (And, three years later, we can now all see that truth. But it was not as obvious to a lot of people in 2006.)

Relating this to our sand pile, the longer that a critical state builds up in an economy, or in other words, the more "fingers of instability" that are allowed to develop a connection to other fingers of instability, the greater the potential for a serious "avalanche."

Or, maybe a series of smaller shocks lessens the long reach of the fingers of instability, giving a paradoxical rise to even more apparent stability. As the late Hunt Taylor wrote, in 2006:

"Let us start with what we know. First, these markets look nothing like anything I've ever encountered before. Their stunning complexity, the staggering number of tradable instruments and their interconnectedness, the light-speed at which information moves, the degree to which the movement of one instrument triggers nonlinear reactions along chains of related derivatives, and the requisite level of mathematics necessary to price them speak to the reality that we are now sailing in uncharted waters.

"... I've had 30-plus years of learning experiences in markets, all of which tell me that technology and telecommunications will not do away with human greed and ignorance. I think we will drive the car faster and faster until something bad happens. And I think it will come, like a comet, from that part of the night sky where we least expect it."

A second related concept is from game theory. The Nash equilibrium (named after John Nash) is a kind of optimal strategy for games involving two or more players, whereby the players reach an outcome to mutual advantage. If there is a set of strategies for a game with the property that no player can benefit by changing his strategy while (if) the other players keep their strategies unchanged, then that set of strategies and the corresponding payoffs constitute a Nash equilibrium.

A Stable Disequilibrium

So we ended up in a critical state of what Paul McCulley called a "stable disequilibrium." We have players of this game from all over the world tied inextricably together in a vast dance through investment, debt, derivatives, trade, globalization, international business, and finance. Each player works hard to maximize their own personal outcome and to reduce their exposure to "fingers of instability."

But the longer we go on, asserts Minsky, the more likely and violent an "avalanche" is. The more the fingers of instability can build. The more that state of stable disequilibrium can go critical on us.

Go back to 1997. Thailand began to experience trouble. The debt explosion in Asia began to unravel. Russia was defaulting on its bonds. Things on the periphery, small fingers of instability, began to impinge on fault lines in the major world economies. Something that had not been seen before happened: the historically sound and logical relationship between 29- and 30-year bonds broke down. Then country after country suddenly and inexplicably saw that relationship in their bonds begin to correlate, an unheard-of event. A diversified pool of debt was suddenly no longer diversified.

The fingers of instability reached into Long Term Capital Management and nearly brought the financial world to its knees.

So, where are the fingers of instability today? Where are the fault lines that could trigger another crisis? Are there any early warning signs? I see two possibilities, one positive and one negative.

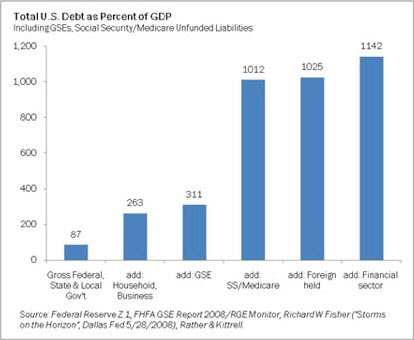

Chad Starliper sent me the following graph. It shows the debt-to-GDP ratio for the US, adding in various levels of debt. For instance, the ratio of debt to GDP for all levels of government debt is 87%. But if you add household and business debt along with the GSE (government-sponsored enterprises) like Fannie and Freddie, the ratio rises to 331%. If you add in future benefits of Social Security and Medicare, the number becomes more like 1,000%.

The Obama administration tells us that the government deficit is going to be well over trillion a year for at least ten years. And that does not take into account the outlier years in the 2020s when the really heavy lifting of Social Security and Medicare kicks in.

There is a truism that goes a little like, "If something can't happen, then it won't." Let me make a prediction. We won't have a trillion-dollar deficit in ten years. Why? Because it can't happen. The market will simply not allow it.

As I have written, we can run large deficits almost forever, as long as the deficits are less than nominal GDP. While it may not be the wise thing to do, it does not bring down the system.

But when you start adding to the deficit in amounts significantly larger than nominal GDP, there is a limit. Each dollar, like the grains of sand, adds to the potential instability of the system. Is it trillion more? trillion? No one can know, but the longer it goes, the worse the ensuing financial earthquake will be.

The current political class and their intentions are dangerously close to killing the golden goose. It is one thing to steal the eggs; it is an altogether different thing to kill the goose through ignorance of the consequences. And the size of the deficit, for as long as they plan to have it, will most assuredly kill the goose.

Just as I was writing in 2006 about the potential for a crisis, and yet the party went on for quite some time, I think the party can limp along now. But there will come a point when the party is over. Interest rates on the long end will rise precipitously, forcing mortgages up and making the deficit even worse. It will be an even worse crisis than the one we have just gone through. And there will be fewer options for policy makers, and none of them will be good or pleasant. And it will take most people unawares. They will see the current trend and project it into the future. And they will be hit hard.

Can we avoid this calamity? Yes, we can wrestle the US budget deficit back under some kind of control, close to nominal GDP or on a clear trajectory to get there within a reasonable time (say, a few years). As noted above, we can run deficits close to nominal GDP almost forever. But there is no political willpower to do that now. And so, the market will at some point force the hand of the political class. That investor in St. Louis, or China or (????) will decide not to buy government debt at such low rates. The avalanche will start. And everyone will be surprised at the ferocity of the crisis. Except you, gentle reader. You have been warned.

Let me re-emphasize that point. If we do not get our act together, the results could be truly serious. And it is not just the US. Japan, as I have written, unless it changes, will hit the wall in the next few years. There are some really sick actors in Europe. You are going to have to be far more nimble and prepared for this next crisis, should it arise, than you were for the last one.

Each week, John Mauldin's free services Outside the Box and Thoughts from the Frontline are read by close to a million investors, so he must be doing something right. Learn more.