It’s been an eventful week in Asia. The world turned its attention and concern to Japan as it copes with the most powerful earthquake in the country’s history. The markets reacted, with Asian shares declining and uranium sentiment negative as investors rethink nuclear power.

We are optimistic that a resilient Japan will turn from tragedy to opportunity by stimulating itseconomy through a reconstruction of the nation. Our thoughts are with the Japanese families searching for loved ones and facing the task of rebuilding their country.

This week, China was recognized for an achievement of its own. The country has resumed the leadership it lost to Britain and then the U.S. more than 165 years ago as the world’s top manufacturing country by output. In 2010, China’s manufacturing output accounted for 19.8 percent of the world’s total—surpassing the U.S. by 0.4 percent.

This growth does not surprise Michael Ding, portfolio manager of the China Region Fund (USCOX), who attended the ROTH Capital Partners conference earlier this week in California. There he met with and listened to numerous CEOs and CFOs from businesses in China across several industries, including materials, energy and industrials. The leaders indicated that their revenue growth rate is in the double digits, access to bond markets and bank lending continues, and business remains robust.

The most important take-away from the conference was that consumer demand remains strong. This is important to China as the country transforms from an export-driven economy to one based on domestic consumption.

Michael’s hands-on report mirrors what BCA Research has to say on the expected continuation of a residential construction boom. BCA says that strong consumer demand mixed with a lack of housing and land supply is supportive for the market.

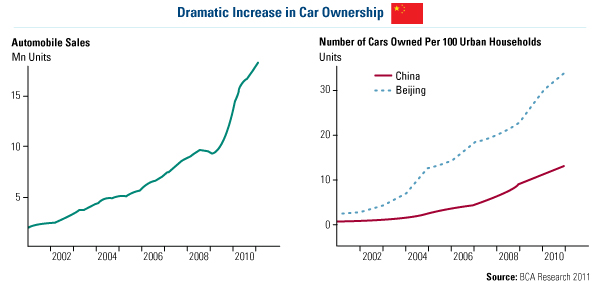

What’s driving this growth? A portion comes from increased car ownership, which has grown from less than 1 percent to 13 percent over the past 10 years. In major cities, such as Beijing, more than 30 out of 100 households own a car.

Total sales rose from just over 2 million units per year in 2001 to roughly 10 million units by 2008. Since then, while much of the global economy has battled recession, automobile sales have risen another 60 to 75 percent.

Compare this growth to the rise of the American suburban family in the 1950s. As automobiles became more common, they transported American families from cities to newly built houses on the outskirts and a suburban boom ensued. The explosion in car ownership means people become more mobile. Chinese families living in urban areas can decide to move farther away from the city in search of newly-built houses with space for parking.

Likewise, people in rural areas can move to the cities. At a rate of nearly 15 million people per year, rural Chinese have been relocating to an urban area. Approximately 15 to 20 percent of the total urban population—or a stunning 35 to 46 million potential families—plan to buy homes within the next three months.

Many of these potential homebuyers have more disposable income to afford an upgrade in their housing situation. Chinese workers have been rewarded with considerable raises in income over the past few years. In 2010, urban incomes rose nearly 8 percent and rural income grew even faster at 11 percent. Their increased wealth has created a demanding consumer who desires the American dream of car ownership and better housing.

To accommodate this demand in the residential market, a tremendous amount of land and construction projects are needed. Currently urban residents make up only 50 percent of the population. If China follows the same urbanization pattern followed by economies such as the U.S., Japan and Korea, this number will climb to 80 percent by 2030, or about 570 million people. That growth implies the development of 10 million residential units every year.

For years to come, we expect China’s urbanization should continue to drive housing growth—and with it, demand for materials and resources needed for these projects.

Foreign and emerging market investing involves special risks such as currency fluctuation and less public disclosure, as well as economic and political risk. By investing in a specific geographic region, a regional fund’s returns and share price may be more volatile than those of a less concentrated portfolio.