I recently wrote an article called Oil Supply Limits and the Continuing Financial Crisis, which has been accepted by the journal Energy. It is still in pre-publication status, but the corrected proof is available for purchase. Because of copyright limitations, I can’t reproduce the article, but I wanted to at least provide a summary.

When I submitted the article, I was asked for five highlights. These are the ones I submitted:

- Reduced oil consumption leads to lower economic growth and less capacity for debt.

- Lower capacity for debt leads to debt defaults, reduced credit, falling home prices.

- Oil supply limits appear to be a primary cause of the 2008–09 recession.

- If world oil supply remains level, more recession can be expected in OECD countries.

- Inadequate demand for high-priced oil is likely to cause much oil to be left in place.

I also submitted an abstract:

Since 2005, (1) world oil supply has not increased, and (2) the world has undergone its most severe economic crisis since the Depression. In this paper, logical arguments and direct evidence are presented suggesting that a reduction in oil supply can be expected to reduce the ability of economies to use debt for leverage. The expected impact of reduced oil supply combined with this reduced leverage is similar to the actual impact of the 2008–2009 recession in OECD countries. If world oil supply should continue to remain generally flat, there appears to be a significant possibility that oil consumption in OECD countries will continue to decline, as emerging markets consume a greater share of the total oil that is available. If this should happen, based on these findings we can expect a continuing financial crisis similar to the 2008–2009 recession including significant debt defaults. The financial crisis may eventually worsen, to resemble a collapse situation as described by Joseph Tainter in The Collapse of Complex Societies (1990) or an adverse decline situation similar to adverse scenarios foreseen by Donella Meadows in Limits to Growth (1972).

An outline of my paper is as follows.

- Introduction

- Reduced oil supply is likely to result in reduced or negative economic growth

- Timing and nature of constriction of oil supply

- Oil prices do not rise without limit, and oil limits may appear as an “oil glut”

- Differences between a growing economy and a declining economy

- Some examples showing ties to the 2008-2009 crisis

- Possible future scenarios

- Conclusion

Below the fold, I explain what the sections cover.

1. Introduction

While oil supply has been roughly level since 2005, neither increasing or decreasing, there is disagreement regarding what the future will hold. In this paper, we consider the scenario in which (1) world oil supply fails to increase, and (2) emerging economies continue to grow rapidly, creating a shortage of oil that acts as a bottleneck for economic growth for OECD countries. This would seem to be similar to the situation that occurred in the 2005-2009 period.

2. Reduced oil supply is likely to result in reduced or negative economic growth

This connection can be seen both through logical reasoning and through academic studies. When oil is in short supply, gasoline and diesel prices tend to rise. The price of food also tends to rise, since oil products are used in producing food. The price of other goods using oil in their manufacture or transport are likely also to rise. People’s salaries don’t rise to match the rise in oil prices, so it becomes necessary for consumers to cut back on discretionary purchases.

In some cases, interest rates may rise as well. In the 2004 to 2006 period, the Federal Reserve raised target interest rates, mentioning rising oil and food prices as a concern. Since salaries do not rise in response to higher interest rates, people’s salaries are likely to be further squeezed by the higher interest rates.

In response to these stresses, consumers could be expected to cut back in many ways. Purchases of new cars and of more expensive homes would be expected to decline, leading to layoffs in auto manufacturing and declining home prices. Consumers would be expected to go out to restaurants less, take fewer vacations, and make cutbacks in other areas that we consider “discretionary spending”. Some may even default on their loans.

According to James Hamilton, all but one of the 11 recessions since World War II have been associated with oil price spikes.

There are many other academic studies showing a connection between oil or energy and economic growth. For example, Dave Murphy and Charles Hall conclude that there is a fundamental limit to economic growth, in that increasing oil supply will require high oil prices, and these high oil prices will in turn undermine economic growth.

3. Timing and nature of constriction of oil supply

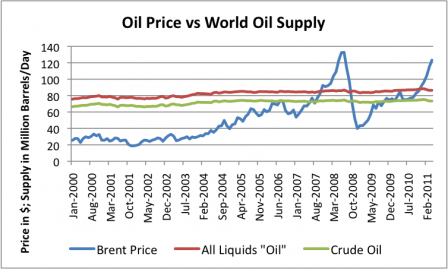

World oil supply has been very close to flat since 2005, despite much higher oil prices than in the period prior to 2005 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. World oil production, compared to Brent price, based on EIA data.

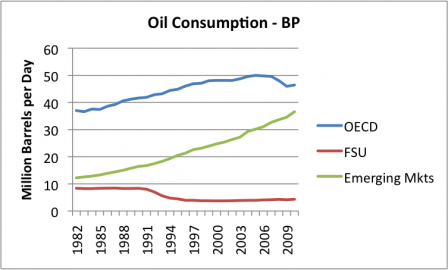

Oil consumption of emerging market countries (which I will define for our purposes as the world, minus the Former Soviet Union, and minus the OECD countries) has been rising rapidly (Figure 2). Since world oil production has been close to flat, the rise in emerging market consumption leaves less for everyone else.

Figure 2. Oil consumption, split between OECD, the Former Soviet Union, and Emerging Markets, based on BP Statistical Data

Oil consumption of OECD countries reached a peak in 2005, and declined between 2005 and 2009, rising again in 2010. The timing of the decline in OECD oil consumption corresponds closely to that of the great recession, with the big declines occurring in 2008 and 2009. Emerging markets, with their rising oil consumption, did not experience recession during this period.

If oil production should remain flat, and if demand from emerging markets (such as China, India, and Middle Eastern oil exporters) should continue to grow, there would appear to be a significant chance that OECD consumption may again fall in the future.

(Note: These graphs are slightly different from those in the paper to avoid copyright issues. They also show more up-to-date data than in the paper.)

4. Oil prices do not rise without limit, and oil limits may appear as an “oil glut”

Quoting from the paper:

In this section we will show that oil prices don’t rise without limit. The constraining factor holding production down is often inadequate demand for high-priced oil, rather than inadequate supply of such oil. The result is what appears to be a “glut” of high-priced oil on the market. If oil were inexpensive, there would be plenty of demand for oil.

Whether or not oil prices can continue to rise indefinitely is important, because if oil prices can rise indefinitely, then there would seem to be a substantial chance that the entire amount of oil resources that have been identified can actually be extracted and used. But if oil prices can only rise to a price of $x before recession sets in, then the majority of oil resources which cannot be economically produced for a price of $x or less will be left in the ground unless at some point in the future, conditions change materially.

Besides high oil prices causing recession, the other issue I identify is the fact that at some point, the price paid for oil will exceed the value received from the oil. It takes oil and other scarce goods to extract the oil. Besides direct costs, the economy will need to keep up its roads, schools, and health care systems, to provide a suitable environment for the workers in the oil system. If too much is spent on oil, there will not be enough funds left for needed services to extract the oil. The equilibrium point will be different, depending on the level of services a country provides. A country such as the US with extensive roads, schools and health care services, would be expected to have a lower equilibrium point (maximum oil price) than a country with less extensive services, such as China or India. This may explain why the oil consumption of emerging market countries can continue to rise, when OECD countries find themselves in recession.

The likely pattern to be observed in oil prices is oscillation–rising oil prices until recession sets in, followed by a decrease in both oil prices and consumption. Eventually, demand rises again, as do prices, until recession sets in again.

5. Differences between a growing economy and a declining economy

In a growing economy, it is much easier to repay loans with interest, because the economy is expanding. If the economy is flat or declining, it is much more difficult.

Figure 3. Two views of future growth

In the article, I describe the relationships algebraically. The basic issues are the same ones I wrote about in my articles The Link Between Peak Oil and Peak Debt – Part 1 and The Link Between Peak Oil and Peak Debt – Part 2.

In this section, I also talk about how a growing economy generates many types of positive feedback loops. Increased debt as well as the growing economy encourage growth in demand for goods and services. Layoffs are relatively rare. Business margins are good, because sales volumes are high relative to fixed costs. Government revenue rises, since tax revenue reflects the prosperity of individual citizens and business owners. Home prices rise because workers can afford to “move up” to more expensive homes. Stock market prices also rise, because of a belief that the favorable conditions will continue indefinitely. It is also relatively easy to borrow money for new investment, so new businesses are formed, further helping employment.

A declining economy works in pretty much the opposite way. With declining demand, the amount of loans outstanding tends to drop (because both borrowers and lenders recognize that it will be harder to repay the loans in a contracting economy, and because businesses have less need for loans to underwrite expansion, when the economy is contracting).

With flat or declining demand and declining loans outstanding, demand for goods and services tends to decline. Layoffs become common, and business margins narrow. Home prices tend to drop, because few people want to move up to more expensive homes, and some may want to move in with friends or relatives. Stock market values are likely to decline, because business prospects decline. Lenders become less willing to offer loans for new investments, because the possibility for repayment are worse. Tax revenues are likely to decline, causing governments to find themselves in increasing financial difficulty.

6. Some examples showing ties to the 2008-2009 crisis

Consumer credit outstanding peaked in July 2008 (Figure 4). That is precisely the month oil prices reached a peak and began to decline.

Figure 4. US consumer credit outstanding, based on Federal Reserve Data

Although I have not shown a graph here, there is a similar relationship with home mortgage loans. The amount of home mortgage loans reached a peak in early 2008, and has been declining every quarter since then.

The downturn in home prices in early 2006 also seems to come at the time one would expect, given rising oil and food prices, and rising interest rates. The rise in oil prices started as early as 2004, (Figure 1) and the Federal Reserve’s response was to raise target interest rates in the 2004-2006 period. While oil prices continued to rise after 2006, sub-prime housing was the “weak link,” and was affected early on by higher oil and food prices together with higher interest rates.

This [the downturn in home prices] came at a time when oil prices were rising, and these higher oil prices affected home-buyers available income, especially in the outer suburbs, where the problem was noticed first.

The US Federal Reserve, in its minutes, specifically referenced rising oil and food prices as reasons for raising target interest rates (Ludlum) [22]. When oil prices rose and interest rates also rose, a reduction in housing demand occurred, which helped prick the sub-prime mortgage bubble.

7. Possible future scenarios

I see three possible scenarios:

Scenario 1. World oil supply again begins to increase, and OECD gets enough of this increase so that its consumption starts increasing. There would be a possibility of few problems, if this should occur.

Scenario 2. There is an increase in world oil supply, but OECD countries are unable to compete for it, or refuse what is available. The outcome can expected to be poor, even if the reduction is voluntary.

Scenario 3. World oil production is flat or declines. It seems likely that OECD will continue to be outbid for oil, and further recession will be likely.

8. Conclusion

We seem to be reaching limits on the amount of oil the world can extract, at prices OECD countries can afford to pay. There appears to be a real possibility that OECD’s oil consumption will continue to decline, and that OECD countries will continue to experience recession and debt contraction.

This could all end very badly. Banks, insurance companies, and pension plans would be adversely affected if debt is not repaid as promised. At some point, the financial system and international trade would appear to be at risk of disruption. Both Tainter (The Collapse of Complex Societies) and Meadows (Limits to Growth) describe adverse scenarios, in which all systems seem to deteriorate at the same time. While we don’t know for certain that the outcome will be of this type, we should be considering this possibility.

Some have suggested that a steady state economy can be developed which will prevent collapse, and allow the world to live at a lower but acceptable level. Research is needed as to whether this is really feasible. It may be that the population which can be supported with a steady state economy does not differ materially from a collapse scenario.

Source: Our Finite World