It's one thing to say that peripheral eurozone countries are better off leaving the euro, but how, exactly? And how severe can we expect the consequences to be, not only for those nations but also for the entire eurozone – and for the rest of us, worldwide? To minimize fallout from the event(s), it would be helpful to have a solid foundation, based on an historical understanding of similar events, on which we could build a reasonable set of expectations.

In the following piece, Jonathan Tepper, my Endgame coauthor, gives us the cornerstone of just such a foundation. With his London firm, Variant Perception, he has prepared a 53-page report with the very confident title "A Primer on the Euro Breakup: Default, Exit and Devaluation as the Optimal Solution."

He reminds us that "during the past century sixty-nine countries have exited currency areas with little downward economic volatility." He makes the case that "The mechanics of currency breakups are complicated but feasible, and historical examples provide a roadmap for exit."

The real problem in Europe, he says, is that "EU peripheral countries face severe, unsustainable imbalances in real effective exchange rates and external debt levels that are higher than in most previous emerging market crises."

The way through? "Orderly defaults and debt rescheduling coupled with devaluations are inevitable and even desirable. Exiting from the euro and devaluation would accelerate insolvencies, but would provide a powerful policy tool via flexible exchange rates. The European periphery could then grow again quickly with deleveraged balance sheets and more competitive exchange rates, much like many emerging markets after recent defaults and devaluations (Asia 1997, Russia 1998, and Argentina 2002)."

We'll need this sort of robust thinking and a willingness to meet the challenge head-on if we're going to get through not just this eurozone crisis but the Endgame in which the whole world finds itself, in the final throes of the Debt Supercycle.

You can see the entire report on the Variant Perception blog – https://blog.variantperception.com/2012/02/16/a-primer-on-the-euro-breakup/– or download it as a PDF.

Your confident that we will master the Endgame analyst,

John Mauldin, Editor

Outside the Box

JohnMauldin[at]2000wave[dot]com

This is an abbreviated version of a longer report which can be accessed at Variant Perception's blog at https://blog.variantperception.com, or as a PDF document. Contact us here to learn more about receiving Variant Perception research as a client.

Summary

Many economists expect catastrophic consequences if any country exits the euro. However, during the past century sixty-nine countries have exited currency areas with little downward economic volatility. The mechanics of currency breakups are complicated but feasible, and historical examples provide a roadmap for exit. The real problem in Europe is that EU peripheral countries face severe, unsustainable imbalances in real effective exchange rates and external debt levels that are higher than most previous emerging market crises. Orderly defaults and debt rescheduling coupled with devaluations are inevitable and even desirable. Exiting from the euro and devaluation would accelerate insolvencies, but would provide a powerful policy tool via flexible exchange rates. The European periphery could then grow again quickly with deleveraged balance sheets and more competitive exchange rates, much like many emerging markets after recent defaults and devaluations (Asia 1997, Russia 19 98, and Argentina 2002).

Key Conclusions

The breakup of the euro would be an historic event, but it would not be the first currency breakup ever – Within the past 100 years, there have been sixty-nine currency breakups. Almost all of the exits from a currency union have been associated with low macroeconomic volatility. Previous examples include the Austro-Hungarian Empire in 1919, India and Pakistan 1947, Pakistan and Bangladesh 1971, Czechoslovakia in 1992-93, and USSR in 1992.

Previous currency breakups and currency exits provide a roadmap for exiting the euro – While the euro is historically unique, the problems presented by a currency exit are not. There is no need for theorizing about how the euro breakup would happen. Previous historical examples provide crucial answers to: the timing and announcement of exits, the introduction of new coins and notes, the denomination or re-denomination of private and public liabilities, and the division of central bank assets and liabilities. This paper will examine historical examples and provide recommendations for the exit of the Eurozone.

The move from an old currency to a new one can be accomplished quickly and efficiently – While every exit from a currency area is unique, exits share a few elements in common. Typically, before old notes and coins can be withdrawn, they are stamped in ink or a physical stamp is placed on them, and old unstamped notes are no longer legal tender. In the meantime, new notes are quickly printed. Capital controls are imposed at borders in order to prevent unstamped notes from leaving the country. Despite capital controls, old notes will inevitably escape the country and be deposited elsewhere as citizens pursue an economic advantage. Once new notes are available, old stamped notes are de-monetized and are no longer legal tender. This entire process has typically been accomplished in a few months.

The mechanics of a currency breakup are surprisingly straightforward; the real problem for Europe is overvalued real effective exchange rates and extremely high debt– Historically, moving from one currency to another has not led to severe economic or legal problems. In almost all cases, the transition was smooth and relatively straightforward. This strengthens the view that Europe's problems are not the mechanics of the breakup, but the existing real effective exchange rate and external debt imbalances. European countries could default without leaving the euro, but only exiting the euro can restore competitiveness. As such, exiting itself is the most powerful policy tool to re-balance Europe and create growth.

Peripheral European countries are suffering from solvency and liquidity problems making defaults inevitable and exits likely – Greece, Portugal, Ireland, Italy and Spain have built up very large unsustainable net external debts in a currency they cannot print or devalue. Peripheral levels of net external debt exceed almost all cases of emerging market debt crises that led to default and devaluation. This was fuelled by large debt bubbles due to inappropriate monetary policy. Each peripheral country is different, but they all have too much debt. Greece and Italy have a high government debt level. Spain and Ireland have very large private sector debt levels. Portugal has a very high public and private debt level. Greece and Portugal are arguably insolvent, while Spain and Italy are likely illiquid. Defaults are a partial solution. Even if the countries default, they'll still have overvalued exchange rates if they do not exit the euro.

The euro is like a modern day gold standard where the burden of adjustment falls on the weaker countries – Like the gold standard, the euro forces adjustment in real prices and wages instead of exchange rates. And much like the gold standard, it has a recessionary bias, where the burden of adjustment is always placed on the weak-currency country, not on the strong countries. The solution from European politicians has been to call for more austerity, but public and private sectors can only deleverage through large current account surpluses, which is not feasible given high external debt and low exports in the periphery. So long as periphery countries stay in the euro, they will bear the burdens of adjustment and be condemned to contraction or low growth.

Withdrawing from the euro would merely unwind existing imbalances and crystallize losses that are already present – Markets have moved quickly to discount the deteriorating situation in Europe. Exiting the euro would accelerate the recognition of eventual losses given the inability of the periphery to grow its way out of its debt problems or successfully devalue. Policymakers then should focus as much on the mechanics of cross-border bankruptcies and sovereign debt restructuring as much as on the mechanics of a euro exit.

Defaults and debt restructuring should be achieved by exiting the euro, re-denominating sovereign debt in local currencies and forcing a haircut on bondholders– Almost all sovereign borrowing in Europe is done under local law. This would allow for a re-denomination of debt into local currency, which would not legally be a default, but would likely be considered a technical default by ratings agencies and international bodies such as ISDA. Devaluing and paying debt back in drachmas, liras or pesetas would reduce the real debt burden by allowing peripheral countries to earn euros via exports, while allowing local inflation to reduce the real value of the debt.

All local private debts could be re-denominated in local currency, but foreign private debts would be subject to whatever jurisdiction governed bonds or bank loans – Most local mortgage and credit card borrowing was taken from local banks, so a re-denomination of local debt would help cure domestic private balance sheets. The main problem is for firms that operate locally but have borrowed abroad. Exiting the euro would likely lead towards a high level of insolvencies of firms and people who have borrowed abroad in another currency. This would not be new or unique. The Asian crisis in 1997 in particular was marked by very high levels of domestic private defaults. However, the positive outcome going forward was that companies started with fresh balance sheets.

The experience of emerging market countries shows that the pain of devaluation would be brief and rapid growth and recovery would follow – Countries that have defaulted and devalued have experienced short, sharp contractions followed by very steep, protracted periods of growth. Orderly defaults and debt rescheduling, coupled with devaluations are inevitable and should be embraced. The European periphery would emerge with de-levered balance sheets. The European periphery could then grow again quickly, much like many emerging markets after defaults and devaluations (Asia 1997, Russia 1998, Argentina 2002, etc). In almost all cases, real GDP declined for only two to four quarters. Furthermore, real GDP levels rebounded to pre-crisis levels within two to three years and most countries were able to access international debt markets quickly.

Historical Currency Exits: Case Studies for the Euro

The Mechanics of a Euro Area Breakup: Lessons from Previous Currency Breakups

The dissolution of the euro would be an historic event, but it would not be the first currency breakup. Some noted economists have called the euro sui generis, or one of a kind. In fact, currency breakups and exits are a common occurrence. Within the past 100 years, there have been over 100 breakups and exits from currency unions.

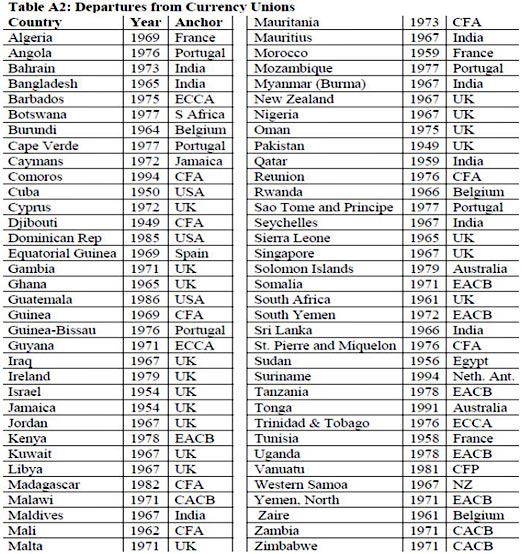

Andrew K. Rose, a Professor of International Business at the University of California, Berkeley, has done a study of over 130 countries from 1946 to 2005. The following table taken from his research gives each exit during the period. In some cases, these were small colonies exiting currency areas and in other cases, these were large countries and currency unions breaking up:

Source: Checking Out: Exits from Currency Unions Andrew K. Rose, 2007 www.mas.gov.sg/resource/publications/staff_papers/StaffPaper44Rose.pdf

The conclusions Andrew Rose draws from the study of all the currency exits are remarkable:

"I find that countries leaving currency unions tend to be larger, richer, and more democratic; they also tend to experience somewhat higher inflation. Most strikingly, there is remarkably little macroeconomic volatility around the time of currency union dissolutions, [emphasis added] and only a poor linkage between monetary and political independence. Indeed, aggregate macroeconomic features of the economy do a poor job in predicting currency union exits."

Source: Checking Out: Exits from Currency Unions Andrew K. Rose, 2007 www.mas.gov.sg/resource/publications/staff_papers/StaffPaper44Rose.pdf

The conclusion - that most exits from a currency union have been associated with low macroeconomic volatility and that currency breakups are common and can be achieved quickly - flies in the face of conventional wisdom.

Any exit from the euro would inevitably re-introduce devalued drachmas, pesetas, escudos, punts or lire, because of extremely overvalued real effective exchange rates and very high net external debt levels. In this context, then, the exit from the euro should be looked at as an emerging market crisis, where countries defaulted on private and/or public debts, abandoned pegs or managed exchange rates, and devalued. The euro merely overlays currency exit to what is a classic emerging market crisis.

Czechoslovakia Breakup: The Velvet Revolution 1992-93

(In this abbreviated report, we will look at one currency breakup. For more currency breakups, please see the following link or visiting our blog at https://blog.variantperception.com.)

Perhaps the most successful, fastest and least eventful currency exit ever was the breakup of Czechoslovakia. Jan Fidrmuc and Július Horváth have analyzed the episode in depth. They argued that the Czech-Slovak joint nation was not an optimal currency area. Depositors and investors from the Slovak side began transferring funds towards the Czech side, much as depositors in the periphery today are transferring deposits from Greek and Portuguese banks to German and French banks. The parallels are uncanny and very instructive.

The process of breaking up was very speedy. It was announced by surprise, and the entire proceedings were concluded within a few months from the announcement.

"During late 1992 and throughout January 1993, many Slovak firms and individuals transferred funds to Czech commercial banks in expectation of Slovak devaluation shortly after the split. Further, Czech exports to Slovakia shot up substantially toward the end of 1992. Czech exports to Slovakia in the last quarter of 1992 rose by 25% compared to the last quarter of 1991. On the other hand, while Slovak exports to the Czech Republic also increased, it was only by 16%. Moreover, in expectation of future devaluation of the Slovak currency, Slovak importers sought to repay their debts as soon as possible while the Czech importers did exactly the opposite. All these developments led to a gradual outflow of currency from Slovakia to the Czech Republic. The SBCS attempted to balance this outflow by credits to Slovak banks, but this became increasingly difficult in December 1992 and January 1993. Thus, the Czech government and the CNB decided already on January 19, 1993 to s eparate the currency. After secret negotiations with the Slovak side, the separation date was set as February 8, 1993, and the Czech-Slovak Monetary Union ceased to exist less than six weeks after it came to being.

"The separation was publicly announced on February 2. Starting with February 3, all payments between the two republics stopped and border controls were increased to prevent transfers of cash from one country to the other. During the separation period between February 4-7 (Thursday through Sunday), old Czechoslovak currency was exchanged for the new currencies. The new currencies became valid on February 8. Regular Czechoslovak banknotes were used temporarily in both republics and were distinguished by a paper stamp attached to the face of the banknote. The public was also encouraged to deposit cash on bank accounts prior to the separation since a person could only exchange CSK 4,000 in cash. Business owners were not subjected to this limit. Coins and small denomination notes (CSK 10, 20 and 50 in the Czech Republic and CSK 10 and 20 in Slovakia) were still used after the separation for several months. Nevertheless, such notes and coins only accounted for some 3% of currency in circulation each. On the other hand, the notes of CSK 10, 20 and 50 accounted for some 45 percent of the total number of banknotes. The stamped banknotes were gradually replaced by new Czech and Slovak banknotes. This process was finished by the end of August 1993."

Source: Stability of Monetary Unions: Lessons from the Break-up of Czechoslovakia, by Jan Fidrmuc, Július Horváth, June 1998 https://ideas.repec.org/p/dgr/kubcen/199874.html

In 1993 Czechoslovakia broke up into two separate states. Shown here is the interim Czech Republic issue of 1000 koruna with control stamp, which circulated only until new notes could be printed.

Source: Keller and Sandrock, "The Significance of Stamps Used on Bank Notes" https://www.thecurrencycollector.com/pdfs/The_Significance_of_Stamps_Used_on_Bank_Notes.pdf

The breakup of the Czech-Slovak Monetary Union was accompanied by a very brief fall in output and trade. Ultimately, the breakup was hugely successful in terms of low macroeconomic costs, as the following analysis from Reuters shows:

"Slovakia had a hard time at first but ultimately became a poster child for reform and qualified for the euro before its neighbour. After contracting 3.7 percent in 1993, Slovakia's economy grew in 1994. Trade between Slovakia and the Czech Republic recovered after a 25 percent drop in 1993 and trade with the European Union grew. The Slovak currency devalued by 10 percent in mid-1993 and remained weaker than the Czech crown until Slovakia's euro entry in 2009.

"'The costs of the event were relatively low and order was quickly restored in both new currency markets," Czech central bank chief Miroslav Singer said in a speech earlier this year.' " [Emphasis added]

Source: Analysis - Czechoslovakia: a currency split that worked, Jan Lopatka, Reuters, Dec 8, 2011 https://uk.reuters.com/article/2011/12/08/uk-eurozone-lessons-czechoslovakia-idUKTRE7B717G20111208

For a complete overview of the breakup of Czechoslovakia's currency union, please see: Stability of Monetary Unions: Lessons from the Break-up of Czechoslovakia, by Jan Fidrmuc, Július Horváth, June 1998 https://ideas.repec.org/p/dgr/kubcen/199874.html

Exiting the Euro: Re-acquiring the Exchange Rate as a Policy Tool

"A nation's exchange rate is the single most important price in its economy; it will influence the entire range of individual prices, imports and exports, and even the level of economic activity."

Paul Volcker and Toyoo Gyohten, Changing Fortunes: The World's Money and the Threat to American Leadership

While each currency exit is unique historically, one can draw some general conclusions:

- What to do with existing currencies – Almost all the case studies continued to use old notes, but mandated that they bear either an ink stamp or a physical stamp. This was the first step in the changeover of notes and coins. Typically, only stamped notes were legal tender during the transitional phase. Once new notes had been printed, old notes were withdrawn from circulation in exchange for new ones. Often old currencies were taken across borders to be deposited into the older, stronger currency.

- Announcements and surprise elements – While almost all devaluations are "surprise" announcements, there is no clear pattern for currency exits. Surprise was important in some cases because, the more advance notice people have, the greater the ability to hoard valuable currency or get rid of unwanted currency. However, countries with less inflation and credit creation and strong political identity were able to avoid surprise, as people were eager to hold the new currencies and get rid of the old, eg the Baltics and the ruble.

- Capital controls and controls on import/export of notes and coins – Allowing notes and currencies move across borders would open up the possibility for leakage of currency and for arbitrage between the old currency and the new currency, depending on expected exchange rates. In most cases, countries imposed capital controls and de-monetized old currency quickly.

- Denomination of cross-border assets and liabilities – In most cases, cross-border liabilities were negotiated in advance by treaty or were assumed to convert at announced exchange rates on the date of the exit.

- Monetary and fiscal independence is crucial once countries exit – The states that introduced new currencies to provide seigniorage revenue to cover fiscal deficits experienced higher inflation and depreciation of their currencies. Countries with independent central banks unable to lend to the government experienced more stable currencies and more stable exchange rates.

There is ample historical precedent for currency union break-ups. They need not be chaotic or have long-term damaging effects. The main caveat is that a full or partial dissolution of the euro would happen with the backdrop of a much more globalized world with a higher volume of cross-border capital flows than previous breakup episodes. In the following section, we use the historical examples we have highlighted above, and how they can be used to guide policy in the event of a breakup of the euro.

Breaking up the Euro: Recommendations Based on Historical Precedents

We recommend that any country exiting the euro should take the following steps:

- Convene a special session of Parliament on a Saturday, passing a law governing all the particular details of exit: currency stamping, demonetization of old notes, capital controls, redenomination of debts, etc. These new provisions would all take effect over the weekend.

- Create a new currency (ideally named after the pre-euro currency) that would become legal tender, and all money, deposits and debts within the borders of the country would be re-denominated into the new currency. This could be done, for example, at a 1:1 basis, eg 1 euro = 1 new drachma. All debts or deposits held by locals outside of the borders would not be subject to the law.

- Make the national central bank solely charged, as before the introduction of the euro, with all monetary policy, payments systems, reserve management, etc. In order to promote its credibility and lead towards lower interest rates and lower inflation, it should be prohibited from directly monetizing fiscal liabilities, but this is not essential to exiting the euro.

- Impose capital controls immediately over the weekend. Electronic transfers of old euros in the country would be prevented from being transferred to euro accounts outside the country. Capital controls would prevent old euros that are not stamped as new drachmas, pesetas, escudos or liras from leaving the country and being deposited elsewhere.

- Declare a public bank holiday of a day or two to allow banks to stamp all their notes, prevent withdrawals of euros from banks and allow banks to make any necessary changes to their electronic payment systems.

- Institute an immediate massive operation to stamp with ink or affix physical stamps to existing euro notes. Currency offices specifically tasked with this job would need to be set up around the exiting country.

- Print new notes as quickly as possible in order to exchange them for old notes. Once enough new notes have been printed and exchanged, the old stamped notes would cease to be legal tender and would be de-monetized.

- Allow the new currency to trade freely on foreign exchange markets and would float. This would contribute to the devaluation and regaining of lost competitiveness. This might lead towards a large devaluation, but the devaluation itself would be helpful to provide a strong stimulus to the economy by making it competitive.

- Expedited bankruptcy proceedings should be instituted and greater resources should be given to bankruptcy courts to deal with a spike in bankruptcies that would inevitably follow any currency exit.

- Begin negotiations to re-structure and re-schedule sovereign debt subject to collective bargaining with the IMF and the Paris Club.

- Notify the ECB and global central banks so they could put in place liquidity safety nets. In order to counteract the inevitable stresses in the financial system and interbank lending markets, central banks should coordinate to provide unlimited foreign exchange swap lines to each other and expand existing discount lending facilities.

- Begin post-facto negotiations with the ECB in order to determine how assets and liabilities should be resolved. The best solution is likely simply default and a reduction of existing liabilities in whole or in part.

- Institute labor market reforms in order to make them more flexible and de-link wages from inflation and tie them to productivity. Inflation will be an inevitable consequence of devaluation. In order to avoid sustained higher rates of inflation, the country should accompany the devaluation with long term, structural reforms.

The previous steps are by no means exhaustive, and should be considered a minimum number of measures that countries would have to take to deal with the transition.

We will later explore which countries are best placed to exit and which ones should stay. Greece and Portugal should definitely exit the euro. Ireland, Spain and Italy should strongly consider it. The countries that should stay in the euro are the core countries that exhibit the highest symmetry of economic shocks, the closest levels of inflation, and have the closest levels of GDP per capita. These countries include: Germany, France, Netherlands, Belgium, Luxembourg, Finland, etc.

Steps for the Countries that Remain in the Euro

The countries that remain within the euro will have to take steps of their own in order to deal with the unilateral exit by a departing country.

- Print new currency – In order to limit large inflows of "old" euros from the any country that has exited the euro, the core countries should print new euros and then de-monetize old euros.

- Recapitalize banks exposed to periphery countries that have exited and defaulted – European banks in the core are already in the process of re-capitalizing, but they would undoubtedly need a much larger recapitalization in the event of periphery defaults.

- The ECB should stabilize sovereign bond yields of solvent but potentially illiquid sovereigns in order to restore stability to financial markets. In order to counteract the inevitable stresses in the financial system and interbank lending markets, central banks should coordinate to provide unlimited foreign exchange swap lines to each other and expand existing discount lending facilities.

Exit, Devalue and Default in Order to Restore Growth

Peripheral Europe: Much Worse than Most Emerging Markets Before a Crisis

The economist Herbert Stein once wrote, "If something cannot go on forever, it will stop." Current dislocations in European credit markets, stock markets and interbank lending rates are unsustainable and are choking periphery economies. The periphery economies cannot continue at such extremes without very deep economic contractions and large scale insolvencies. Without the European Central Bank, most banks in Europe's periphery would not be able to fund themselves. If the situation continues to deteriorate, it would imply an extremely deep recession that would rival or exceed the Great Financial Crisis of 2008.

The PIIGS (Portugal, Ireland, Italy, Greece and Spain) have built up very large unsustainable net external debts in a currency they cannot print or devalue. Each peripheral country is different, but they all have too much debt. Greece and Italy have a high government debt level. Spain and Ireland have very large private sector debt levels. Portugal has a very high public and private debt level. Greece and Portugal are arguably insolvent and will never be able to pay back their debt, while Spain and Italy are likely illiquid and will need help rolling their upcoming debt maturities.

The problem for the European periphery is not only that debt levels are high, but that almost all the debt is owed to foreigners. As Ricardo Cabral, Assistant Professor at the Department of Business and Economics at the University of Madeira, Portugal, points out, "much of these countries' debt is held by non-residents meaning that the governments do not receive tax revenue on the interest paid, nor does the interest payment itself remain in the country":

"In fact, external indebtedness is key to understanding the current crisis. Portugal, Ireland, and Spain have similar external debt dynamics to that of Greece. espite netting out debt-like assets held by residents abroad, the PIGS' average net external debt-to-GDP ratio, is approximately 30 percentage points higher than the average gross external debt-to-GNP ratio observed in the emerging market external debt crises."

Source: The PIGS' external debt problem, Ricardo Cabral, May 2010 https://voxeu.org/index.php?q=node/5008

The following chart shows the net external debt to GDP ratios in Asia before the 1997 crisis, for example.

Source: The PIGS' external debt problem, Ricardo Cabral, May 2010 https://voxeu.org/index.php?q=node/5008

Periphery debt levels before the recent European crisis began in 2010 were much higher than Asia's debt levels before the widespread defaults and devaluations in 1997. The total net external debt of the peripheral countries far exceeded even the highest net external debt seen during the Asian Crisis of 1997. The ratios have since continued to deteriorate. It is also noteworthy that most of the government debt of Greece, Portugal, and Ireland is held abroad, and almost half Spanish and Italian government debt is held abroad.

Source: The PIGS' external debt problem, Ricardo Cabral, May 2010 https://voxeu.org/index.php?q=node/5008

In the case of Asian countries, most of the debt was denominated in another currency, ie dollars. This produced an "inverted balance sheet". With inverted debt, the value of liabilities is positively correlated with the value of assets, so that the debt burden and servicing costs decline in good times and rise in bad times. Once Asian currencies started to depreciate, their debt to GDP ratios skyrocketed. Fortunately, for the European periphery, all the debt is in euros. This is one reason why staying in the euro makes short term sense. Any exit from the euro and move to local currencies that could be depreciated would increase the total debt burden.

In order to finance the large current account deficits, the European periphery has had to sell more assets to foreigners than it purchased. Staggeringly, for Portugal, Greece, Ireland and Spain, foreigners own assets worth almost 100% of GDP. Like a drug addict selling all the family silverware, the periphery has sold large chunks of their assets to fund sustained current account deficits.

The following chart show the evolution of the Net International Investment Position of the periphery and how it has deteriorated to extreme levels.

Source: Bank of Spain, https://bit.ly/rvHs2g and Goldman Sachs, European Weekly Analyst Issue No: 11/44 December 21, 2011 Goldman Sachs Global Economics, Commodities and Strategy Research

Clearly the trend started with the advent of the euro and has deteriorated almost every single year thereafter. Interestingly, as the periphery's NIIP deteriorated, Germany's improved. Germany is the flipside of the periphery. This is highly significant for reasons we discuss below.

Too Much Debt: The Only Way Out Is Devaluation, Inflation or Default

"I've long said that capitalism without bankruptcy is like Christianity without hell." – Frank Borman, Chairman of Eastern Airlines

The net external debt positions and net international investment positions of the periphery countries are extremely high. Indeed, they are so high, historically almost all countries that had such levels have defaulted and devalued. (See This Time Is Different: Eight Centuries of Financial Folly by Reinhart and Rogoff)

When people or companies have too much debt, they typically default. When countries have too much debt, governments have one of three options:

- They can inflate away the debt.

- They can default on it.

- They can devalue and hurt any foreigners who are holding the debt. This is really just a variant of inflating it away.

The ECB cannot pursue inflationary policies or monetize government debt according to its charter. Peripheral countries, thus, owe very large amounts of money in a currency they can't print. Because they are in a currency union, they lack the tools typically available to countries that need to rid themselves of debt. Defaults, then, are the only option. However, defaulting would not solve the underlying problem of a one size fits all monetary policy. Defaulting, exiting the euro and devaluing would be necessary as well.

Optimum Euro Configuration Post-Exit: Who Should Exit?

"People only accept change when they are faced with necessity and only recognize necessity when a crisis is upon them." – Jean Monnet

Greece and Portugal should definitely exit the euro. Ireland, Spain and Italy should strongly consider it. Portugal and Greece are the countries that the market has already marked as being at high risk for exit and default. These happen also to be the countries that have 1) the highest levels of debt and 2) the most overvalued real effective exchange rates. Ireland, Spain and Italy have many of the pernicious characteristics of Greece and Portugal. The market has simply assigned lower probability so far of default and exit to them. This could quickly change and would likely make it even more difficult for them to remain solvent.

One way to think of dividing up the periphery is to distinguish two country profiles:

- Countries with very large current account deficits together with unsustainable level of external debt (Greece, Portugal, Ireland, Spain and Italy). In these cases an orderly default and exit/devaluation are the solution.

- Countries with sizable current account imbalances with a somehow sustainable debt level. In these cases the solution is no default with a one-time parity adjustment, and a devaluation.

Unfortunately, almost all the European periphery falls into camp one, where the best solution is default and devaluation.

What Happens to the Economy After Exit?

Macroeconomic Consequences: Recent Experiences of Defaults and Devaluation

"The only function of economic forecasting is to make astrology look respectable." – John Kenneth Galbraith

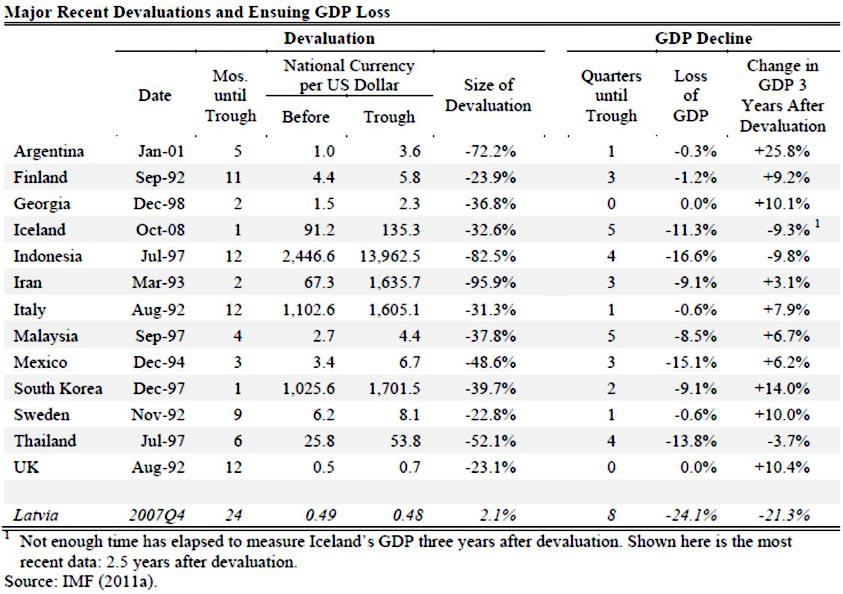

It is useful to look at previous historical examples of countries after they defaulted and devalued to observe their growth and inflation trajectory.

Dire predictions about economic growth following devaluations are invariably wrong, and most countries quickly recover pre-crisis levels of GDP. If we look at recent devaluations, in almost all cases where countries devalued, they had short, sharp downturns followed by steep, prolonged upturns. Mark Weisbrot and Rebecca Ray prepared a report for Center for Economic and Policy Research and examined GDP declines before and after devaluations. The following chart from their study shows where each country's GDP was three years after these large, crisis-driven devaluations. Almost all of the countries are considerably above their pre-devaluation level of GDP three years later.

Source: Latvia's Internal Devaluation, Mark Weisbrot and Rebecca Ray December 2011 www.cepr.net/documents/publications/latvia-2011-12.pdf

Devaluations typically work because if they come after periods of price stability, devaluation can have real effects due to rigidities and money illusion. It can create improved economic sentiment arising from strong demand, higher export profits and temporary employment increases in the short run when wage rigidities can be relied on.

Conclusion

This paper has shown that many economists expect catastrophic consequences if any country exits the euro. However, during the past century sixty-nine countries have exited currency areas with little downward economic volatility. The mechanics of currency breakups are complicated but feasible, and historical examples provide a roadmap for exit. The real problem in Europe is that EU peripheral countries face severe, unsustainable imbalances in real effective exchange rates and external debt levels that are higher than most previous emerging market crises. Orderly defaults and debt rescheduling coupled with devaluations are inevitable and even desirable. Exiting from the euro and devaluation would accelerate insolvencies, but would provide a powerful policy tool via flexible exchange rates. The European periphery could then grow again quickly, much like many emerging markets after recent defaults and devaluations (Asia 1997, Russia 1998, and Argentina 2002). The experience of emerging market countries after default and devaluation shows that despite sharp, short-term pain, countries are then able to grow without the burden of high debt levels and with more competitive exchange rates. If history is any guide, the European periphery would be able to grow as Asia, Russia and Argentina have.

This is an abbreviated version of a longer report which can be accessed at Variant Perception's blog by clicking on the following link or visiting our blog at https://blog.variantperception.com. Contact us here to learn more about receiving Variant Perception research as a client.